Introduction↑

While my last post on the matter was pretty critical on the topic of Scala (and functional programming in general), this post aims to point out the things I actually like, after having used Scala more or less daily for 4 months or so.

I’ll go through some cherry-picked features and design patterns that stand out to me as actually, genuienly, bona-fide useful in my day-to-day job as a Data Engineer - and no, I am not talking about Spark.

This isn’t a tutorial, nor an exhaustive list - more so, a follow-up that outlines some things I found neat, rather than talking about the things I find annoying.

Re-wiring your brain for types over logic↑

I have talked about the importance of data types at length before, in the context of plain old organization and metadata, static vs dynamic typing, or in the context of more traditional ETL pipelines.

With the prevalence of interpreted, dynamically typed languages, such as Python, it’s somewhat easy to consider types as an afterthought while designing your program, which is not to be confused with the notion that types are not important - but they are not regarded as the most important thing. I’d wager to say that every Python programmer will agree that types are, in fact, important, but the way FP tends to re-wire your brain is what struck me as particually valuable in procedural and/or OOP programming, as well as in FP: Type-driven programming (a name inspired by this talk).

Scala has rewired my brain enough, so that I tend to think of types first, everything else second, rather than approach a problem via, say, OOP design patterns to give myself a baseline.

Composition↑

Let me illustrate this with an example. How do we approach solving a problem? Rarely, I’d wager, by simply starting to fill in a function (or class) body without thinking about structure and composition, maybe even abstraction, at least for a bit.

Take the following prompt (a Leetcode example, despite my burning hatred for these brain teasers, it works well to illustrate a point):

Given a roman numeral, convert it to an integer.

This simple prompt gives us the outline for our program (without further details and constraints), which we can design without thinking about the implementation yet:

- “Given a…” tells us about a function that accepts an input.

This seems trivial - and a function that doesn’t accept an input is technically not a function - but in OOP-languages, the following is a perfectly valid pattern:

abstract class RomanNumeral { public int toInteger() // reads from an instance member variable}-

“…roman numeral…” tells us about a specific type for our function, in this case a “Roman Numeral”, whatever that means

-

”…, convert it…” tells us about what our function needs to do

-

“…to an integer…” tells us about our output type

The latter is another great example of something that seems - and, again, is, trivial, but also confusing: Side-effects. A function ought to return something, and a function ought to be pure (or, like my mathematician friends would snarkily say, “should be actually a function”). But, once again, in OOP land, this is perfectly reasonable:

abstract class RomanNumeral { private int result; public void toInteger(); // ... public int getInteger(); // ...}Here, toInteger would mutate the state of the class RomanNumeral (hence returning void), and getInteger would return the result. This can be a perfectly valid design choice.

Through a functional lens, however, the following signature emerges:

def romanNumeralToInteger(roman: RomanNumeral): Int = ???This function signature encapsulates, unambiguously, the entirety of the exercises’ prompt, without diving into any implementation details of the actual problem.

A procedural or polymorphic approach isn’t wrong, just different↑

This “types-first” approach isn’t necessarily better than designing a polymorphic (or subtyping) hierarchy around a problem, or approaching a problem by scaffolding empty methods; for instance, we could structure our approach towards the problem by simply outlying some procedural placeholders, with or without types.

I do find the following a valid strategy for a first pass - at the very least, in order to solve this problem, we need to make sure we check, then parse the given input. So, we might get away with 2 functions that roughly outline what we need to do:

# Make sure it's a Roman numeral; throw an exception otherwise, maybe?def validate_input(s): pass

# Translate it (...)def roman_to_int(s): passOf course, we can now easily add type hints after the fact:

def validate_input(s: str) -> bool: passWhat I’ve liked thinking in FP is that by approaching types first, rather than second, you’re forced to think through your code’s possible paths a lot more than if you don’t; having a compiler that enforces this behavior certainly also helps.

As for the argument that unit testing can replace strong typing, consider the common refactoring practice in strongly typed languages: Changing the type of an argument of a particular function. In a strongly typed language, it’s enough to modify the declaration of that function and then fix all the build breaks. In a weakly typed language, the fact that a function now expects different data cannot be propagated to call sites. Unit testing may catch some of the mismatches, but testing is almost always a probabilistic rather than a deterministic process.

Testing is a poor substitute for proof.

Milewski, Bartosz: Category Theory for Programmers

Let’s take a look at the specific types - and why the ever-present String is a bad one - to illustrate this point.

Domain Models↑

We’re in a bit of a pickle with the previous scaffolding around validate_input, even though you might not realize it: validate_input expects a String! The issue is, the entirety of “War and Peace” by Tolstoy is a String if you want it to be, but certainly not a roman numeral.

So let’s consider domain models as types.

This general idea, unsurprisingly, is nothing new for OOP programmers: You general do create custom classes to model your application; most people, however, tend not to model types, but rather stateful, mutable objects that, while themselves having a type signature, are a much more complicated construct.

Replacing a seemingly trivial type like String with a custom type seems excessive; in fact, even Leetcode’s very own examples use String in every language for the expected signature:

Java:

class Solution { public int romanToInt(String s) {

}}TypeScript:

function romanToInt(s: string): number {

};And even Ruby, with its very awkward type annotations:

# @param {String} s# @return {Integer}def roman_to_int(s)

endNaturally, this makes things easier. But the prompt implicitly models constraints: “ABC” is not a roman numeral. Roman numerals have a finite set (an alphabet) of characters: (I, V, X, L, C, D, M), to be precise and they have composability rules of their own. “ABC” is a String, but decidedly not a Roman Numeral, and henceforth, a different type.

In the simplest of cases, we alias the type to make the signature clear:

type RomanNumeral = StringThis helps the human, but the compiler will still happily take Russian literature as a RomanNumeral.

We can also take that one step further and declare the following, using refinement types:

type RomanNumeral = NonEmptyStringOr, we can build out a custom domain model:

case class RomanNumeral(value: String)And even model some of these constraints:

object RomanNumeral { val alphabet = Set('I', 'V', 'X', 'L', 'C', 'D', 'M') def apply(s: String): Option[RomanNumeral] = s match { case v if v.toCharArray.count(c => alphabet.contains(c)) == v.length => Some(new RomanNumeral(v)) case _ => None }}Scala doesn’t have the notion of constrained types, so our constructor returns an Option[RomanNumeral], rather than a RomanNumeral (since throwing an Exception make the function impure).

Which poses another design question: How much logic should a domain model contain? In this example, we validate the characters, but validating the input is at least 50% of this exercise.

In any case, this model is relatively clear: Under the hood, you still have a String - which is great for interoperability - but also a clear type constructor with clearly modeled behavior.

An alternative is to decomposite this even further and use an Algebraic Data Type (ADT), one of the most delightful FP features, specifically a sum type:

trait RomanCharacter case object I extends RomanCharacter case object V extends RomanCharacter case object X extends RomanCharacter case object L extends RomanCharacter case object C extends RomanCharacter case object D extends RomanCharacter case object M extends RomanCharacterThis looks slightly less odd in Haskell:

data RomanCharacter = I | V | X ...And change our RomanNumeral constructor to accept this ADT instead:

case class RomanNumeral(value: RomanCharacter*)val example1 = RomanNumeral = RomanNumeral(X, I, V) // validval example2: RomanNumeral = RomanNumeral(I, I, I, I) // also valid, but nonsenseval example3: RomanNumeral = RomanNumeral(A, I, V) // Cannot resolve symbol AWhich doesn’t model the logic, but allows us to define a type that, by itself, is composed of logically sound elements, in this case Roman Characters. It is now impossible to use invalid characters while creating a RomanNumeral type.

At this point, we can come back to the question I posed earlier: How much logic should my domain model contain? Should you be able to create a RomanNumeral from IIII? Should it yield RomanNumeral(I,V) or not?

I can’t answer this question for you - in my opinion, it’s a question of style, rather than logic - but in my opinion, a type should be as unambiguous and logically sound as possible. Therefore, RomanNumeral(I,I,I,I) should not be possible. But if we want to, we now can adjust our model to use a companion object to return an Option[RomanNumeral], rather than one directly, just as we did before.

My biggest takeaway here is: Treating models as types (again, types first) makes your code much easier to read, reduced the possibility for errors, and is all of a sudden much more useful - at least subjectively - than writing endless POJOs for no apparent effect. And this goes both ways: When writing, as well as when reading code.

Understanding code by reading types↑

The same thing also helps tremendously when reading code you didn’t write. I’m going to push this example a little too far - in the real world, you would of course actually read the docs, and also be expected to know about stuff like effects - but the overall message should still ring true: Scala makes it pretty easy to understand somebody else’s code and library (and allows for logical composition) - if they use clear type signatures. Once we have a type signature, we can reason about a function.

Category theory is about composing arrows. But not any two arrows can be composed. The target object of one arrow must be the same as the ource object of the next arrow.

In programming we pass the results of one function to another. The program will not work if the target function is not able to correctly interpret the data produced by thesource function. The two ends must fit for the composition to work.

The stronger the type system of the language, the better this match can be described and mechanically verified.

Milewski, Bartosz: Category Theory for Programmers

Combine this with composition: f :: A -> B and g :: B -> C put together as g(f(a) only works if the types match. Keep this in mind, since we’ll be looking at Java code that doesn’t do this at the end here, or at least not directly, and observe how neatly the Stream fits together (and how the compiler won’t let you stitch something together that doesn’t make sense!).

Take a look at this function from fs2-kafka, which is a library to treat Apache Kafka as a stream, using the fs2 library for streams. Their docs point out a lot of examples, but don’t mention this method anywhere:

trait KafkaConsume[F[_], K, V] { def partitionedStream: Stream[F, Stream[F, CommittableConsumerRecord[F, K, V]]] // ...Without necessarily going into the details, this simple signature itself tells us a lot about what this function does (I should add that the library does have plenty of docstring in reality) and how to use it. We already know the following from looking at those 2 lines:

- The trait is called

KafkaConsume, so it’s reasonable to assume that this is a thing that consumes messages from Kafka. Good naming standards still apply. - With that knowledge, we can assume that the generics

KandV- which follow standard naming patterns for generic types - are the types ofKeyandValue, which how mostKafkastreams are organized. - We can recognize

F[_]as a higher-kinded type (a type constructor), that describes “the type of a type”; since this isn’t very descriptive in itself, we can hunt down what this means in a second. For now, we know that this trait is, for all intents and purposes, very generic (and flexible) type that somehow goes along the Key/Value pair. Since Kafka itself doesn’t expect anything but Key/Value (e.g.,[String,Int]for a message like"key":100), it’s probably got something to do with how we talk to Kafka. More in a second. - The function itself, like any good OOP or procedural function name, tells us that it will give us a partitioned stream; if we know something about Apache Kafka, we know that Kafka distributes its records in a finite number of partitions, using a deterministic hashing logic, so this function should give us access to each of those partitions.

- We see its return type and see that it returns a

Stream, which is good, since we’re working in a streaming library. We’re now back to the type constructor,F[_], sinceStreamtakesFas a type parameter. What isF? At this point, we need to look one level deeper and figure out howStreamactually looks and deconstruct this beast fromfs2:

final class Stream[+F[_], +O] private[fs2] (private[fs2] val underlying: Pull[F, O, Unit])- This is arguably much nastier looking, but only on the surface; first of all, we’ll ignore everything

private- if it’s private, then there’s an API we’re supposed to use and read. Maybe this is cheating for the purists, but it’s how I actually read and write code, and that’s what this is about. Anyways, our IDE can help us find usages ofStream, and the simplest is the companion object’s constructor:

def apply[F[x] >: Pure[x], O](os: O*): Stream[F, O] = emits(os)// For all intents and purposes, an overloaded function/alias, so let's check out `emits`def emits[F[x] >: Pure[x], O](os: scala.collection.Seq[O]): Stream[F, O]- Which now tells us more about what we want from

F- the symbol<:indicates a recursive type signature, also known as F-bounded polymorphism, or in my head, simply “type bounds”:F[X]needs to be a supertype ofPure[X], which is an alias totype Pure[A] <: Nothing- a type that has no effects (as the word “pure” indicates). - If you’re familiar with

cats, you already knew this, but this should de-mystify the whole signature:Fis the effect type, andOis the output type (since we’re creating this from a scala collection of typeO). - Reading these handful of lines thus far should give us knowledge equivalent to the following lines from the docs:

[…]

Streamis fully polymorphic in the effect type (theF[_]inStream[F, A]), as long asF[_]is compatible with thecats-effecttypeclasses.…

[…] Its output type is of course

Int, and its effect type isPure, which means it does not require evaluation of any effects to produce its output. Streams that don’t use any effects are called pure streams.

- Back to

partitionedStream: The effect of this can be any of cat’s typeclasses. When in doubt, it’sIO, the most basic effectful type incats-effect- since it can’t bePure, since we’re talking toKafka, an external service.

More on cats and effects below..

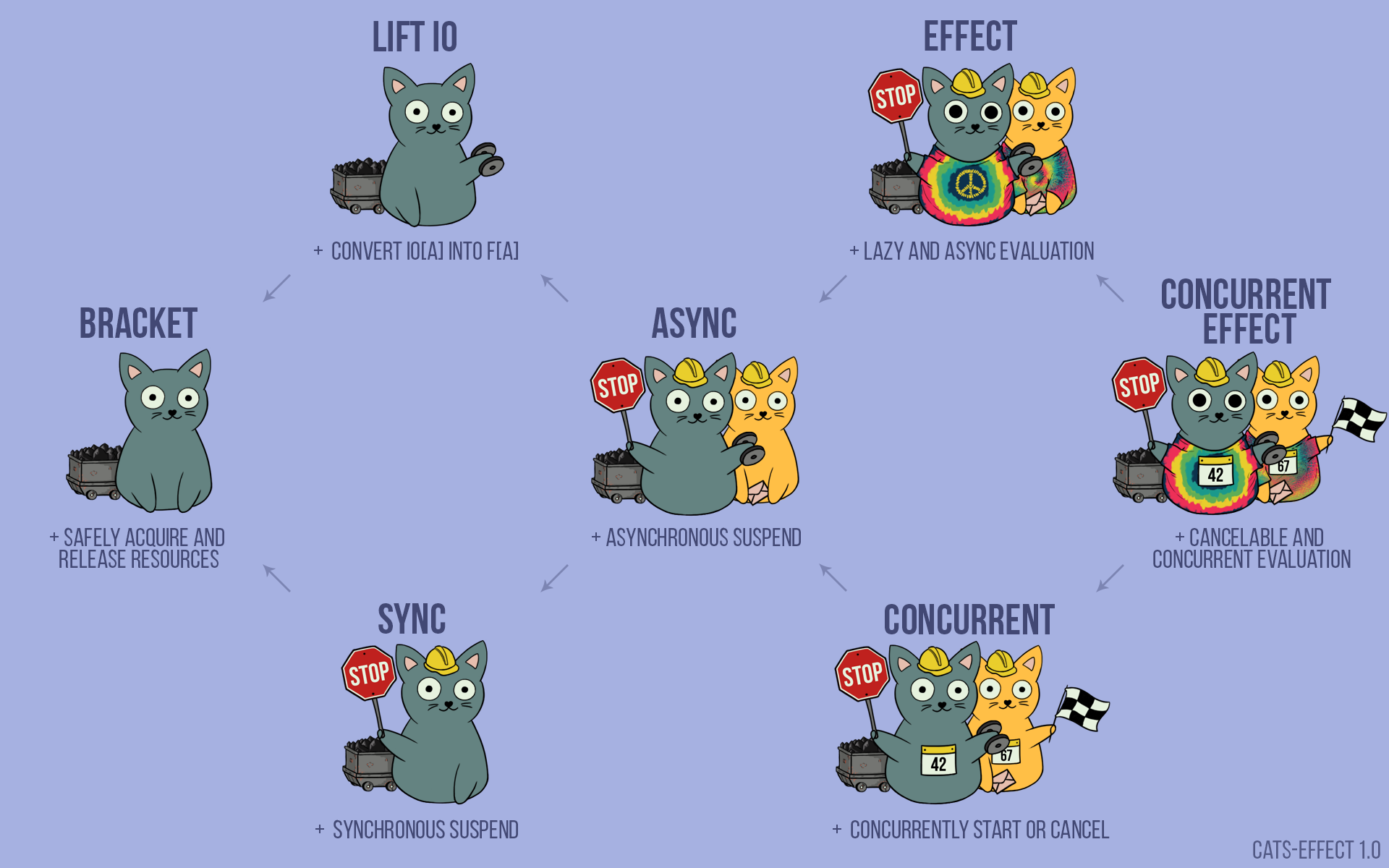

(Credit: Credit: https://typelevel.org/cats-effect/docs/2.x/typeclasses/overview)

- For simplicity, let’s asume:

Stream[IO, Stream[IO, CommittableConsumerRecord[IO, K, V]]] - Understanding our effect type, let’s look at our output type: And that would be another Stream! The second stream uses the same effect, but its output is of type

CommittableConsumerRecord, which is also anIO, and takes anyK/Vpair - as we’ve established before, these probably refer to a key and a value in a Kafka stream.

Now, what good does this knowledge do us? Well, I can quickly write code that does something that the docs don’t outline explicitly (something that’s very difficult if your type signatures are unclear), without stealing it from StackOverflow, purely based on these type signatures:

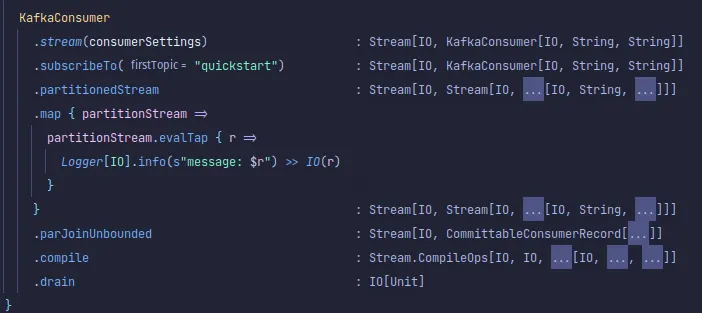

KafkaConsumer .stream(consumerSettings) .subscribeTo("quickstart") .partitionedStream .map { partitionStream: fs2.Stream[IO, CommittableConsumerRecord[ IO, String, String ]] => partitionStream.evalTap { r: CommittableConsumerRecord[IO, String, String] => Logger[IO].info(s"message: $r") >> IO(r) } } .parJoinUnbounded .compile .drainThis will take a Kafka stream, go through each partition, and print each record without altering the effect - not very useful, granted, but the docs do not give an example on how to use this function - since they don’t have to. I’ve had the compiler annotate the types more than usual here, so you can see where our types show up again.

IntelliJ also inlines the types for you:

Naturally, this code also simply won’t compile if your types don’t match; it can’t compose the functions.

Of course, this isn’t the entire story; in this example, you’re dealing with an infinite stream of data, with side-effects, with the particularities of a distributed message broker system and its particularities, such as consumer groups, offset management, configuration, zookeeper, etc. etc. You still have some work left to do yourself!

So I’m not saying “types solve programming for you” - but what I am saying is that I have a much easier time understanding libraries that I’ve never seen before in a language that I am objectively still mostly unfamiliar with by simply untangling their types, rather than trying to go for the docs first thing.

Not every library is as well-documented as fs2 and its little Kafka brother, and Google results for Scala tend to be 90% Spark - so speaking the language you’re supposed to speak is pretty neat.

Finally, let me contrast this with the standard Kafka Java library, without composition, clear effects, and Map<String,String> for everything:

public class ConsumerExample {

public static void main(final String[] args) throws Exception { // ...

final String topic = "purchases"; // Load consumer configuration settings from a local file // CH: This can throw! In FP-land, this is an IO final Properties props = ProducerExample.loadConfig(args[0]); // Add additional properties. // CH: All of these are Strings - and constants and/or enums are the closest we have to ADTs // CH: It's also all mutable and changing the same object reference // CH: The validation of the domain model here is difficult - a composable function like `.withGroupId(groupId)` makes this much clearer props.put(ConsumerConfig.GROUP_ID_CONFIG, "kafka-java-getting-started"); props.put(ConsumerConfig.AUTO_OFFSET_RESET_CONFIG, "earliest"); // Add additional required properties for this consumer app final Consumer<String, String> consumer = new KafkaConsumer<>(props); // CH: This is your main effect - your reference to your consumer object is now subscribed to a remote broker, but it returns a void, not indicating what's really happening consumer.subscribe(Arrays.asList(topic)); // CH: I think of "try...catch" as `def try(f: => Unit)` - just *very* ambigiously // CHL This is essentially a `Stream[Resource, K, V]` try { while (true) { ConsumerRecords<String, String> records = consumer.poll(Duration.ofMillis(100)); for (ConsumerRecord<String, String> record : records) { String key = record.key(); String value = record.value(); System.out.println( String.format("Consumed event from topic %s: key = %-10s value = %s", topic, key, value)); } } } finally { consumer.close(); } }}This is easy to read, no doubt - but it isn’t nearly as easy to build, since I have nothing forcing me to have my next step in the chain to be of the correct type. And that’s were composition + reading types is a benefit to cherish.

However, some types do not lend themselves to good type signatures. I will leave you with this: While we all know what it’s meant to do, we cannot reasonably discern in which direction filter works by just looking into the type signature.

def filter(p: A => Boolean): List[A]Boolean isomorphism: Nobody really cares, but you could reasonably argue we should care. :)

Implicits & Type Classes↑

Another really fun thing Scala can do is this little thing called implicit:

A method can have an implicit parameter list, marked by the implicit keyword at the start of the parameter list. If the parameters in that parameter list are not passed as usual, Scala will look if it can get an implicit value of the correct type, and if it can, pass it automatically.

Implicit↑

What this means is the following: Given a function like map here:

sealed trait Tree[A] { def put(v: A): Tree[A] def has(v: A): Boolean def get(v: A): Option[A] def map[B](f: A => B)(implicit o: Ordering[B]): Tree[B]}The parameter o is tagged as implicit; most (if not all) Trees (as in the math-y ones, not the ones outside) need to know how to order values. If I define a generic Tree trait that takes any type A - which we know nothing about - we need to somehow tell it how to order values. We could have a Tree[String], but also a Tree[Tuple2[BigDecimal,Long]] - both of which don’t have an inherent way of ordering (just because everything defaults to lexicographical order for Strings, that doesn’t make it correct).

We can now either call:

RBTree[Int]().map(t: Int => t.toString)(scala.math.ordering.Int)and pass the order directly, which is fine for one-off function calls. But Scala allows me to have an implicit value in scope and simply say:

import scala.math.ordering.Int/// lots of codeRBTree[Int]().map(t: Int => t.toString)Which will apply my Ordering to my Tree. In other words, we said:

“Type

Aneeds to be a type that can be ordered”

Similarly, I can make use of the scope hierarchy of implicits and build myself something like this:

case class CustomNewType(value: Long)object CustomNewType { implicit val order: Ordering[Long] = scala.math.ordering.Long}Which will “package” my implicit scope in the companion object of my domain model.

While this is useful - and easily abused - it becomes really valuable once we look at type classes, which take the idea of specifying details on types to a different level.

Type classes↑

Allow me to use Haskell as an example for type classes real quick:

A typeclass is a sort of interface that defines some behavior. If a type is a part of a typeclass, that means that it supports and implements the behavior the typeclass describes. A lot of people coming from OOP get confused by typeclasses because they think they are like classes in object oriented languages. Well, they’re not. You can think of them kind of as Java interfaces, only better.

Lipovača, Miran: Learn You a Haskell for Great Good!

As a matter of fact, the only way to overload a function in Haskell is to use type classes.

In “real-world” Scala, I found myself using type classes mostly for encoding and serializing. circe, for instance, has been a regular companion of mine.

Take the following model:

case class Id(value: PosLong)case class UserName(value: NonEmptyString)case class User(id: Long, name: String)We can turn this into a JSON object:

val user: User = User( Id(refineMV[Positive](1L)), UserName(refineMV[NonEmpty]("admin")))val json: String = user.asJson.noSpacesprintln(json)// {"id":1,"name":"admin"}Without writing any code for this specific model by using type classes. Once we take a look at asJson:

implicit final class EncoderOps[A](private val value: A) extends AnyVal { final def asJson(implicit encoder: Encoder[A]): Json = encoder(value) final def asJsonObject(implicit encoder: Encoder.AsObject[A]): JsonObject = encoder.encodeObject(value)}You can see the implicit encoder here. By using some other fun libraries that use compiler macros and other tricks - derevo and newtype - we can actually get this implicit encoder generated for us by using some annotations in the model:

object Model { @derive(encoder, decoder) @newtype case class Id(value: PosLong) @derive(encoder, decoder) @newtype case class UserName(value: NonEmptyString) @derive(encoder, decoder) sealed case class User(id: Id, name: UserName)}For all intents and purposes, it appears that my User class now has a new method, asJson.

In Java land, the decompiled class looks like this - you can see the encoder and decoders that are needed for asJson:

❯ javap Model\$User$Warning: File ./Model$User$.class does not contain class Model$User$Compiled from "Model.scala"public class example.Model$User$ implements java.io.Serializable { public static final example.Model$User$ MODULE$; public static {}; public io.circe.Encoder$AsObject<example.Model$User> encoder$macro$5(); public io.circe.Decoder<example.Model$User> decoder$macro$6(); public example.Model$User apply(java.lang.Object, java.lang.Object); public scala.Option<scala.Tuple2<java.lang.Object, java.lang.Object>> unapply(example.Model$User); public example.Model$User$();}The neat thing is, this also works with any other class. Say we want a filterValues function for any generic Map:

object Implicits { implicit class MapOps[K, V](private val value: Map[K, V]) { def filterValues(f: V => Boolean): Map[K, V] = value.filter(kv => f(kv._2)) }}This allows us to do:

Map("a" -> 1, "b" -> 2).filterValues(_ >= 2)Which is a very neat feature, which I have come to love, but don’t view as the only way of doing things (by not being a purist on the topic) - rather a very useful tool.

The IO monad & cats-effect at large↑

The arguably more important use for type classes in my day-to-day, however, is the cats-effect library. I’ve mentioned it above.

Cats Effect is a high-performance, asynchronous, composable framework for building real-world applications in a purely functional style within the Typelevel ecosystem. It provides a concrete tool, known as “the

IOmonad”, for capturing and controlling actions, often referred to as “effects”, that your program wishes to perform within a resource-safe, typed context with seamless support for concurrency and coordination. These effects may be asynchronous (callback-driven) or synchronous (directly returning values); they may return within microseconds or run infinitely.

While this description sounds somewhat obscure at first - once I got a baseline understanding of why I care about declaring effects - I severely miss them in other languages.

Effects exists in any language, and while we might not know the definition of the term, we know what it means:

The term Side effect refers to the modification of the nonlocal environment. Generally this happens when a function (or a procedure) modifies a global variable or arguments passed by reference parameters. But here are other ways in which the nonlocal environment can be modified. We consider the following causes of side effects through a function call:

- Performing I/O.

- Modifying global variables.

- Modifying local permanent variables (like static variables in C).

- Modifying an argument passed by reference.

- Modifying a local variable, either automatic or static, of a function higher up in the function call sequence (usually via a pointer).

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Side_effect_(computer_science)#cite_note-Spuler-Sajeev_1994-1

Javascript, Typescript, and scala: Telling the same story↑

Allow me to illustrate by means of a bit of Javascript:

const baseURL = 'https://api.sampleapis.com/beers/ale';function getBeer() { return fetch(baseURL) .then(function (res) { return res.json(); }) .then(function (res) { return res; });}This tells us nothing: Ignoring the (in this example, purposefully) bad function name, we have no idea on its return type. Even if we could somehow say function getBeer // returns an object as Beer{price: }..., or even better, model a Beer struct, we still have no clue about failure conditions or anything that could happen out of the ordinary. Is this function pure? Unless you declare something const, stuff is mutable in JS. Does this function talk to the outside world? What are the failure conditions when it does so? If it does so, do we treat an HTTP 500 differently than a 404? Every time we use getBeer, do we evaluate it? Do we block? Do we need to try-catch it?

Since using a language that treats types as more of an abstract idea is probably unfair, let’s use Typescript:

interface Beer { price: string name: string // ...}

const baseURL = 'https://api.sampleapis.com/beers/ale';function getBeer(): Promise<Beer[]> { return fetch(baseURL) .then(res => res.json()) .then(res => { return res as Beer[] })}getBeer().then(b => console.log(b))(In case this isn’t obvious, this is the code the original Javascript example was compiled from)

The thing I want to focus on is the function signature. Keep in mind that this is the exact same thing as the JS code:

function getBeer(): Promise<Beer[]>A Javascript Promise is probably the closest thing to a functional effect in JS that someone who read a book about JS about 6 years ago can come up with. Promise, I’d argue is almost the equivalent to an IO monad: It’s a wrapper - a data structure - around an effect with the outside world, doing IO. You could argue that flatMap and then aren’t that different here. Somebody took this idea so seriously that they created an Algebraic JavaScript Specification.

Anyways - what this signature tells us is the same thing that this cats signature tells us:

def getBeer(): IO[Beer] = // ...getBeer().flatMap(b => Logger[IO].info(b) >> IO.unit)It lets me know that an IO[Beer] isn’t necessarily a Beer.

First of all, this:

val ioMonad: IO[Unit] = getBeer().flatMap(b => Logger[IO].info(b) >> IO.unit)Does nothing without something actually running the effect, such as unsafeRunSync (it is lazy).

/*** Produces the result by running the encapsulated effects as impure side effects.** If any component of the computation is asynchronous, the current thread will block awaiting* the results of the async computation. By default, this blocking will be unbounded. To limit* the thread block to some fixed time, use `unsafeRunTimed` instead.** Any exceptions raised within the effect will be re-thrown during evaluation.** As the name says, this is an UNSAFE function as it is impure and performs side effects, not* to mention blocking, throwing exceptions, and doing other things that are at odds with* reasonable software. You should ideally only call this function *once*, at the very end of* your program.*/final def unsafeRunSync()(implicit runtime: unsafe.IORuntime): A = unsafeRunTimed(Long.MaxValue.nanos).getSecondly, the type - also just like a Promise in JS - informs me that Beer is not a pure function: It has side-effects.

Lastly, once I’m within an IO (or any other effect), we can’t escape it. We can’t say:

def getBeer(): IO[Beer] = // ...getBeer().getValue // <- this doesn't existBut what we can say is:

for { b <- getBeer() // IO[Beer] => Beer _ <- Logger[IO].info(s"Soup of the day: $b")} yield bWhich of course is just sugar for:

getBeer() .flatMap(b => Logger[IO].info(s"Soup of the day: $b") .map(_ => b) )In both cases, the result of this computation is always an IO[Beer], despite me using the wrapped type within a log statement. The flatMap call merely evaluates the effect, and fails fast once it encounters an error.

Sometimes, being forced to do things one way can greatly improve code quality; once you’re dealing with (relatively) large code bases, with a lot of interactions with the outside world (think REST, GraphQL, databases, Kafka …), there is no ambiguity about what can fail - which is the ultimate question of a clean control flow.

More than IO: Embracing cats at large↑

IO as a baseline type - a type much more decoupled in cats-effect 3 than in 2 - is cool. But once you dip your toes into the more specialized types, you will quickly realize how ambiguous your previous code was, and that this notion of declaring - and subsequently, treating - non-pure things differently than pure things, is pretty neat.

Here’s the cats + cats-effect type class library in version 3:

The typeclass hierarchy within Cats Effect defines what it means, fundamentally, to be a functional effect. This is very similar to how we have a set of rules which tell us what it means to be a number, or what it means to have a

flatMapmethod.

Let’s go back to the fs2-kafka example from earlier: Instead of getting a Stream, we can also get a Resource:

def resource[K, V](settings: ConsumerSettings[F, K, V])( implicit F: Async[F], mk: MkConsumer[F]): Resource[F, KafkaConsumer[F, K, V]] = KafkaConsumer.resource(settings)(F, mk)Which is a thing that requires a finalizer to use it - think with() statements in many languages, such as Python - such as opening a file, where you don’t want dangling file descriptors.

Or, maybe you need to handle errors in different scenarios: cats’ MonadError, a type all effects use, allows me to handle the an Exception with getBeer gracefully:

getBeer().flatMap(b => Logger[IO].info(s"Soup of the day: $b") .map(_ => b))).handleErrorWith(t => Logger[IO].error(s"Oops: $t") >> IO.pure("Soda"))Or, I can use guaranteeCase to model more complex failure scenarios:

getBeer() .flatMap(b => Logger[IO].info(s"Soup of the day: $b") .map(_ => b) )).guaranteeCase { case c if c.isSuccess => Logger[IO].info(s"Beer!: $c") case c if c.isCanceled => Logger[IO].info(s"The tap broke") case _ => Logger[IO].info(s"Oh no :(") } .handleErrorWith(t => Logger[IO].error(s"Oops: $t") >> IO.pure("Soda"))// 20:52:56.218 [io-compute-11] INFO example.Hello - Oh no :(// 20:52:56.221 [io-compute-11] ERROR example.Hello - Oops: java.lang.Exception: No beer// or// 20:53:39.042 [io-compute-11] INFO example.Hello - Soup of the day: beer// 20:53:39.047 [io-compute-11] INFO example.Hello - Beer!: Succeeded(IO(beer))Or, to sum it up:

Code the happy path and watch the frameworks do the right thing.

Volpe, Gabriel: Practical FP in Scala

Conclusion↑

Ultimately, I am still very much a novice with cats and cats-effect if I compare myself with somebody who is intimately familiar with their underlying concepts, but I’ve already embraced their logical extension onto the praise I’ve given the type-driven programming that FP made me embrace.

There is, of course, more to this story; just because I can create something resembling an ADT in Python doesn’t necessarily mean I’ll do it, because the syntax is awkward and an afterthought. On a similar note, if performance is paramount, having to deal with the overhead of objects (that are not newtypes) on the JVM for a bit of type clarity isn’t always preferable.

But there are enough functional concepts that have at least the potential to make me a better developer, and those are the ones I’ll continue to try and embrace, since (as outlined) many of the concepts do transfer to OOP and procedural languages.

Of course, there’s plenty of things I don’t like, but those aren’t the topic of today’s discussion; I do like things, occasionally, and I outlined some here today.

All development and benchmarking was done under GNU/Linux [PopOS! 22.04 on Kernel 5.17] with 12 Intel i7-9750H vCores @ 4.5Ghz and 32GB RAM on a 2019 System76 Gazelle Laptop, using scala 2.13.8