Introduction↑

INFO

Other parts in this series:

➡️ Part 1: Building a functional, effectful distributed system from scratch in Scala 3, just to avoid Leetcode

➡️ Part 3: Job submission, worker scaling, and leader election & consensus with Raft

It’s been a while since I wrote about Bridge Four, my Scala 3 distributed data processing system from scratch.

In this article, we’ll be discussing some major changes around Bridge Four’s state management, its new-and-improved consistency guarantees, and other features and improvements I’ve added since.

In case you haven’t read the previous article, I suggest you do that. You can do that here.

Overview↑

A recap on Bridge Four↑

As a super quick recap, Bridge Four simple, functional, effectful, single-leader, multi worker, distributed compute system optimized for embarrassingly parallel workloads.

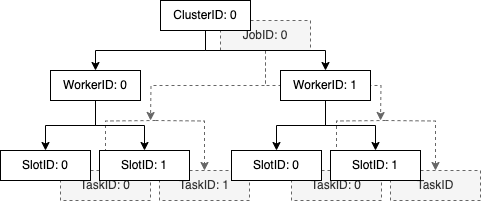

ID Overview.

(Credit: Christian hollinger)

Its general semantics are

- Single leader, multi-worker

- Eventually consistent (see below)

- Redundant workers, SPOF in the leader

- “Self”-healing (workers can be killed and re-started during execution, the leader will recover)

This is a rough overview:

System Overview.

(Credit: Christian hollinger)

And for some terminology:

- A job reads files, performs computations, and writes output files

- Each job executes N tasks (N > 0)

- Each task executes on a worker (aka a

spren) - Each worker has a set number of slots with each can execute exactly 1 task in parallel

- The leader is called

kaladin

And the name is inspired by Brandon Sanderson’s “The Stormlight Archive”.

The open issues with Bridge Four↑

There is an original list of issues in v0.1 of the repo, which you are free to browse. It left a lot to be desired, and frankly, still does.

So while many of those issues remain, but I’d like to think that the changes I’ve made (and will go over shortly) alleviated several of them and paved the way for more and more “big boy” features, such as self-healing or even leader election to get rid of that pesky single point of failure.

The Changelog↑

The biggest changes are around the API semantics - moving from a “pull” system to a background worker - and the resulting consistency guarantees that weren’t really defined beforehand.

In summary:

- The cluster now accepts a job and will, at its own leisure, assign it to workers and take care of it

- Kaladin has a background worker system that updates state

- …and a cache that users query

- …and therefore, users no longer need to force a refresh by calling

GET -> / refresh(hence, no more “pull” semantics) - …and, by proxy, much better internal abstraction and compartmentalization (there even is a

ReadOnlyPersistencetrait) - A much simpler ID system

- More private constructors and applies

- Fewer leaky abstractions

- No more state machines that shouldn’t be there

- Full Docker support

- Scripts that larp as integration tests

- Updated persistence logic

- More / Different API calls

So, let’s go over them more-or-less chronologically, so you can actually look at useable git diffs.

Note: I usually rage on about how nobody does semantic versioning correctly and this case, I’m unfortunately no better. All these “minor” version increases caused breaking changes.

v0.2: General Cleanup↑

The first big change since the original project. 444 additions and 356 deletions, mostly focussed on cleaning up spaghetti code that were introduced during the original implementation, while I was trying to do everything at once.

Much simpler ID system↑

One of the biggest refactors was around the sheer amount of ID tuple types that existed in the system.

Originally, this grew organically to model all the relationships in isolation.

Recall:

ID Overview.

(Credit: Christian hollinger)

We’re basically dealing with 2 tree-type data structures, one for the Cluster (in white), and one for the job (in grey), which is one level shallower, since a job is not aware of where it’s running.

Since different components were dealing with different IDs, actually passing this tree-type structure around was proving difficult (although I might go back to that), so the original ID system was a bit… wild.

Here’s one simple example that got rid off the not-so-super-ergonomic SlotTaskIdTuple:

state <- Resource.make(InMemoryPersistence.makeF[F, Long, FiberContainer[F, TaskState, SlotTaskIdTuple]]())(_ => mF.unit) bgSrv = BackgroundWorkerService.make[F, TaskState, SlotTaskIdTuple](state) Resource.make(InMemoryPersistence.makeF[F, Long, FiberContainer[F, BackgroundTaskState, TaskId]]())(_ => mF.unit )bgSrv = BackgroundWorkerService.make[F, BackgroundTaskState, TaskId](state)I won’t call our more individual changes for this - but rest assured, they are out there.

Private constructors and applies↑

Many data models were lacking calculated attributes. For instance, mapping a ExecutionStatus to whether a slot within a worker is available for a new task, rather than making that a function of the model itself.

case class SlotState( id: SlotIdTuple, available: Boolean,// A SlotState is reported by a worker. They are unaware of what exactly they are working on. The state is ephemeral.// The leader keeps track of it persistently.case class SlotState private ( id: SlotId, status: ExecutionStatus) derives Encoder.AsObject, Decoder Decoder {

def available(): Boolean = ExecutionStatus.available(status)

}In addition to that, few constructors were private, pushing the burden of providing reasonable defaults onto the caller when calling apply(). This revision uses more opinionated constructors.

object SlotState {

def started(id: SlotIdTuple, taskId: TaskIdTuple): SlotState = SlotState(id, false, ExecutionStatus.InProgress) def apply(id: SlotId, status: ExecutionStatus): SlotState = new SlotState(id, status = status)

def empty(id: SlotIdTuple): SlotState = SlotState(id, true, ExecutionStatus.Missing) def started(id: SlotId, taskId: TaskIdTuple): SlotState = SlotState(id, ExecutionStatus.InProgress)

def empty(id: SlotId): SlotState = SlotState(id, ExecutionStatus.Missing)

}There is nothing magical about those fixes - they are the “can’t see the forest for the tree”-type oversights solo-projects (especially larger/more complex ones) tend to accumulate.

Fewer leaky abstractions↑

This iteration also removed the TaskExecutionStatusStateMachine, which was never really a state machine. In the original version, it would try to model def transition(initialSlot: SlotState, event: BackgroundWorkerResult[_, TaskState, SlotTaskIdTuple]): SlotState on a worker, i.e. have the worker itself keep track of the ExecutionStatus of its tasks.

Now, now, the TaskExecutor simply handles any error on probing the execution status, since the expectations for jobs is (and has been) to implement def run(): F[BackgroundTaskState], i.e.:

override def getSlotState(id: SlotIdTuple): F[SlotState] = bg.probeResult(id.id, sCfg.probingTimeout).map(r => taskStateMachine.transition(SlotState.empty(id), r))override def getSlotState(id: SlotId): F[SlotState] = bg.probeResult(id, sCfg.probingTimeout).map { r => r.res match // The "result" for this operation is just another ExecutionStatus from the underlying task case Right(res) => SlotState(id, status = res.status) case Left(status) => SlotState(id, status = status) }This makes the state system considerably easier. Every time the leader prompts its workers for an updated status, the worker will either:

- Have a result available and hence, an appropriate

Donestatus returned by the job (i.e.,BridgeFourJob). Please note that theBridgeFourJobis still as terrible as in the original and hence, should probably not do that either. - Be aware of the task, but won’t have a result, so

BackgroundWorkerwill return aInProgressstatus - Not be aware of the task, so

BackgroundWorkerwill return aMissingstatus - Be aware of a failure, so

BackgroundWorkerwill return anErrorstatus

And, related to the previous point, the WorkerState model now simply maps a WorkerStatus - an ADT for “alive” or “dead” - in the model itself:

case class WorkerState private ( id: WorkerId, slots: List[SlotState], status: WorkerStatus = WorkerStatus.Alive)// ...def apply(id: WorkerId, slots: List[SlotState]): WorkerState = { val allSlotIds = slots.map(_.id) val status = if (slots.isEmpty) WorkerStatus.Dead else WorkerStatus.Alive new WorkerState(id, slots, status)}Cluster Status↑

GET -> / cluster has been added and gives an overview about the entire cluster:

{ "status": { "type": "Healthy" }, "workers": { "0": { "id": 0, "slots": [ { "id": 0, "status": { "type": "InProgress" } }, "..." ], "status": { "type": "Alive" } }, "1": "..." }, "slots": { "open": 0, "total": 4 }}Docker support + Chaos Monkey↑

I’ve also added docker-compose support, albeit relatively barebones, which makes testing easier.

And while that technically happened in v0.3, the original Docker support was added here.

Running sbin/wordcount_chaos_money.sh, for instance, will submit a job, let it start, assign all tasks to all workers, and then murder spren. While the deadeyes are staring aimlessly into the void (if this sentence confuses you, I suggest spending a minute or two to read ~5,000 pages of “The Stormlight Archive”), it’ll re-spawn one worker and the job will continue in a degraded cluster state:

Started job -351033585{"type":"NotStarted"}Worker 1{"id":0,"slots":[{"id":0,"status":{"type":"Done"}},{"id":1,"status":{"type":"Done"}}],"status":{"type":"Alive"}}Worker 2{"id":1,"slots":[{"id":0,"status":{"type":"Done"}},{"id":1,"status":{"type":"Done"}}],"status":{"type":"Alive"}}Sleeping for 10 seconds{"type":"InProgress"}Killing on port 6551c3cf1775936eWorker 2{"id":1,"slots":[{"id":0,"status":{"type":"InProgress"}},{"id":1,"status":{"type":"InProgress"}}],"status":{"type":"Alive"}}Sleeping for 10 seconds{"type":"InProgress"}Killing on port 6552313ba30a7fb4Sleeping for 20 seconds{"type":"InProgress"}Restartingbridgefour-spren-01-1Sleeping for 20 seconds{"type":"InProgress"}{"type":"Done"}Job doneChecking resultsCleaning upTowards the end, the cluster status will look a little something like this:

{ "status": { "type": "Degraded" }, "workers": { "0": { "id": 0, "slots": [], "status": { "type": "Dead" } }, "1": { "id": 1, "slots": [ { "id": 0, "status": { "type": "InProgress" } }, "..." ], "status": { "type": "Alive" } } }}But the job will still finish. Resilience!

v0.3: Architectural changes & Consistency↑

This section is (arguably) more interesting with 869 additions and 1208 deletions. This changed the job submission and data retrieval mechanism and consistency guarantees of the system. Some of the number of changes is also attributed to a cleanup of the pseudo integration tests / examples in sbin, which now exclusively use docker.

New Persistence logic↑

InMemoryPersistence now uses a Ref (rather than the somewhat limiting MapRef and hence, Persistence also supports

update(identity: V)(key: K, v: V => V): F[Unit]keys(): F[List[K]]values(): F[List[V]]list(): F[Map[K, V]]

Furthermore, I’ve split Persistence into ReadOnlyPersistence[F[_], K, V] and Persistence[F[_], K, V] extends ReadOnlyPersistence[F, K, V], which makes the bold assumption/simplification that ReadWrite is a superset of ReadOnly. This does, however, help to narrow down who can write to the shared state.

Note: This should probably be done with typeclassses, although I do like the obvious (idiomatic) pragmatism of just mixing in some OOP inheritance to simply the type system and leave most typeclasses for the effect framework. Over-abstraction being not very grug-brain-like and all that.

Self portrait.

(Credit: grugbrain.dev)

New API calls↑

Thanks to that new functionality, this added the Kaladin call GET -> jobs / list to list running jobs.

I also replaced the underlying implementation of Kaladin call GET -> / status and with GET -> / refresh, since they both return ExecutionStatus, but GET -> / status could be stale. Despite being a public API, is really an implementation detail at this point, as you’ll see in the next section.

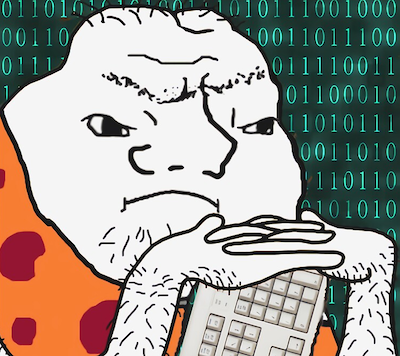

Changed the semantics and responsibilities for managing cluster and job state↑

The original implementation had a somewhat Schroedinger’s state mechanism under the hood by relying on a pull mechanism to poll for state w/in the leader - if you don’t ask for an update on a job, the leader won’t try to talk to the workers to get a result and such, remain blissfully ignorant.

This is an actual problem, since without a user calling / refresh, while not all tasks in a job might be done (or a worker might have crashed etc. etc.), no further tasks are being assigned.

As such, a job’s lifecycle used to be “Start” => “Refresh” =?> “Get Job Status” =?> “Get Data”, i.e.:

![Starting a Job [Before]](/_astro/DistributedSystem-StartJob.drawio.zomWhopL.png)

Starting a Job [Before].

(Credit: Christian Hollinger)

In this version, everything else is handled by Kaladin in a background thread, meaning after you start a job you can repeatedly call “Get Data” (or just ask for ExecutionStatus) until a result is being returned.

![Starting a Job [Now]](/_astro/DistributedSystem-StartJob.drawio.blGKeL_C.png)

Starting a Job [Now].

(Credit: Christian Hollinger)

Kaladin now has background threads↑

Implementation wise, ClusterController is a new program that will do three main functions in regular intervals and persist each operations’ result into the cache:

- Update the cluster status

- Update all job states

- Rebalance unassigned tasks to workers

Semantics wise, this is a wee bit awkward, since def run[F[_]: Async: Parallel: Network: Logger](cfg: ServiceConfig) operates on Resource, so we do Resource.make(clusterController.startFibers())(_ => Async[F].unit).start.

startFibers is a F[Unit] that calls foreverM[B](implicit F: FlatMap[F]): F[B] = F.foreverM[A, B](fa) on an internal function that does all three functions above (wrapping them in ThrowableMonadError[F].handleErrorWith) and then calls a Sync[F].sleep for that fiber. This could probably done better with something like fs2… but it works. Since it returns F[Unit], there should be no StackOverflows in my future.

If you’re wondering why I didn’t re-use the BackgroundWorker, that is simply because this a fire-and-forget semantic, rather than a stateful background worker queue.

At the end of the day, we now have 2 main programs that use several of the underlying algebras or services:

ClusterControllerdoes the background task above and does the heavily liftingJobControllercontrols the external interface towards users and barely modifies state (more on that in a second)

Keep in mind that each program is a clean abstraction that could, conceptually, be its own micro service.

Also, WorkerOverseer merged with HealthService into ClusterOverseer, since they basically did the same thing.

You now submit a job, you do not start one↑

The original implementation with the single program, JobController, accepted a job config, validated it, and synchronously had the leader (where the config was submitted to) talk to all available workers accept said job, after making decision(s) on how to assign the tasks.

In this version, you now simply submit a job to JobController, which returns immediately; that means, JobControllerService only accepts submissions jobs and otherwise reads from the shared cache.

@EventuallyConsistentdef submitJob(cfg: UserJobConfig): F[JobDetails]A submitted job will persist an def initialState(jCfg: UserJobConfig): F[JobDetails] result into the shared cache. ClusterController, during its periodic scans, will pick up that thus far unassigned job and do the heavy lifting: Split the job, assign it to available workers, etc.

All other available methods here simply read from the shared cache.

This has the distinct advantage that they all return results within milliseconds (since the leader doesn’t need to talk to the cluster and deal with pesky things like retries and timeouts), we have no need for advanced locking mechanisms (the Persistence implementations are concurrency safe), and that we could deploy multiple API services for load balancing reasons, but at the explicit cost of freshness.

In other words, all operations on JobController are now eventually consistent (or worse).

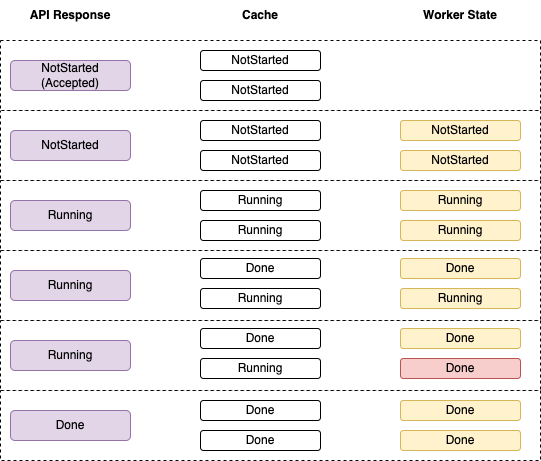

Talking about Consistency↑

The internals ClusterController are actually strongly consistent now. It achieves that by doing it the (old-school) redis way by being effectively single threaded for writes, by using a global Mutex[F] against all three public functions. Since neither of these functions are public as in “on a user facing API”-public, but rather run by Kaladin itself in the background, having contention issues here is not a problem.

However, the interactions with the users now have eventual consistency guarantees. I use the word “guarantee” a bit liberally here. I think you could argue the bespoke API (talking to the leader only) actually strongly consistent.

It’s most certainly not linearizable - the order of events is neither guaranteed, nor deterministic, and a re-play in the order of events cannot be guaranteed - but asking Kaladin what the status of the job is will always report the leader’s current view on the world.

That view, however, might already be outdated, since tasks might have finished in the background since Kaladin upgraded the cache. If you were to talk to the workers (which you shouldn’t do directly, but certainly can), you would get a different view on the world.

This example illustrates this:

Consistency.

(Credit: Christian Hollinger)

Only after a while will they all converge and tell the same story.

Once a user submits a job and the cluster (more specifically, the leader) accepts their job, it means that eventually, at some point in the future and most certainly not right now, the job will be executed and the resulting data will be given back to the user.

In case you’re wondering, yes, I am basically describing cache misses. But if you’ve ever worked on and/or designed a (globally) distributed system with caching, you’d probably get to the conclusion that those are indeed some of the most realistic consistency challenges your everyday, not-building-a-database-from-scratch engineer will encounter.

Next Steps & Conclusion↑

I’ve trying to hold myself to writing shorter articles that one can actually reasonably read on a lunch break, so we’ll leave it with version 0.3 for now.

Out of the original list of issues, I’d say at least “Consistency guarantees” and “State machine improvement” are somewhat adequately covered here.

Next time, we’ll cover

Global leader locks: The

BackgroundWorkeris concurrency-safe, but you can start two jobs that work on the same data, causing races - the leader job controller uses a simpleMutex[F]to compensate

Which will give us a chance to talk about global mutexes and atomicity.

I’ve also been toying with the idea of throwing tracing in the mix to show the actual tree the cluster generates and how data flows from A to B. I do have a Grafana instance floating around somewhere…

I’ve also been reading Gabriel Volpe’s “Functional Event-Driven Architecture” (available here), which also has some really neat ideas I could shoehorn into here. I will say, however, that I’d like to stick to the “everything from scratch, no existing libraries like Kafka”-mantra that I outlined in part one.

If time permits, and I’m only writing this here so I can hold myself to it is to improve on the self-healing and discoverability abilities of the cluster. As the Chaos Monkey example demonstrates, as long as a worker comes back online, the cluster will continue to function.

The issue with that, however, is that the exact same machine with the exact same IP and port needs to come online, since that is hard-coded in the config. The cluster also currently starts, but will crash on the first actual discovery call to the workers if they are misconfigured (e.g., Kaladin thinks there’s a spren with ID 0 at port 5551, but 5551 reports ID 1). The secret magic is almost as clever as the Spanning Tree Protocol: implicitly[ThrowableMonadError[F]].raiseError(InvalidWorkerConfigException(s"Invalid worker config for id $wId")) (in case you’ve been paying attention, yes, this crashloops forever).

Wouldn’t it be neat to ARP into the void and see if there’s a shy little worker somewhere on the network willing to take on tasks? This would, by proxy, also give us the basic mechanic ✨ autoscaling ✨ , which I believe would make this “enterprise ready”.

Code is available on GitHub

All development and benchmarking was done under MacOS 14.2 (Sonoma) with 12 M2 arm64 cores and 32GB RAM on a 2023 MacBook Pro