Introduction↑

Google Play Music joined its brethren in the Google Graveyard of cancelled products in late 2020. Having used Google Play Music many years ago to back up all my MP3 rips (I collect CDs and Vinyl and have done so for about 17 years), Google sent me several friendly emails, asking me to transfer my music to YouTube Music and/or use Google Takeout to download a copy.

I did the latter. Little did I know that what I would receive would rival even the most horrifying “We’ve been doing reporting in Excel for 12 years!”-type datasets I’ve seen throughout the years.[1] This is an attempt to tell the story on how I approach badly documented, rather large datasets from a Data Engineering lense and how I turned a dump of data into something useful.

This article will pretend we’re not just organizing some music, but rather write a semi-professional, small-sized (~240GB in total) data pipeline on bare metal, with simple tools. During this, we’ll be working with a fairly standard Data Engineering toolset (bash, go, Python, Apache Beam/Dataflow, SQL), as well as work with both structured and unstructured data.

(My little KEF LS50 in front of the CDs that started this whole journey)

(My little KEF LS50 in front of the CDs that started this whole journey)

[1] The cynic in me thinks that this is intentional (in order to push you to YouTube Premium) - but I would not be surprised if Google has a perfectly valid Engineering reason for this mess.

All code can be found on GitHub!

Making Sense of it: The Google Play Music Takeout Data↑

Before we even try to attempt to formalize a goal here, let’s see what we’re working with. I should add that your mileage may vary - I only have my export to work with here.

Export Process↑

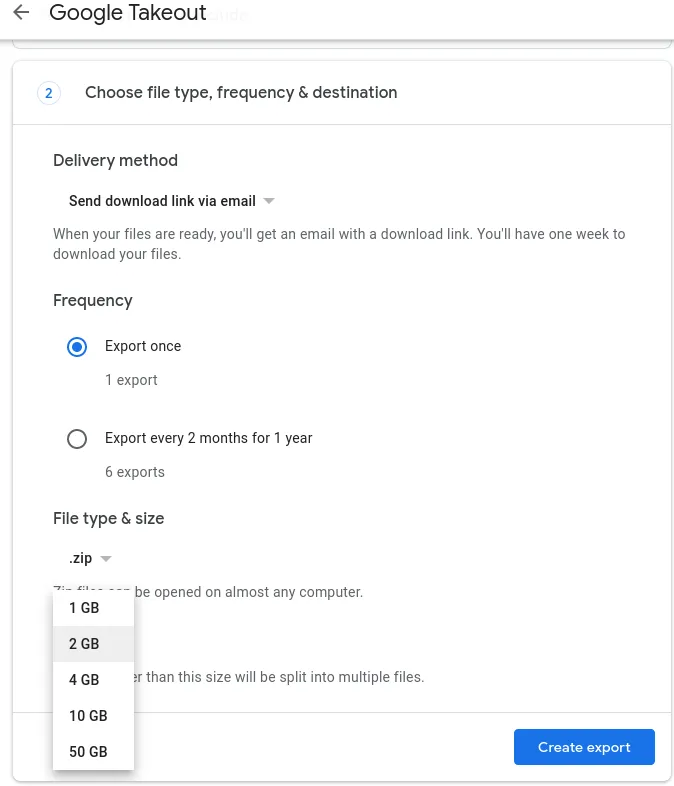

Exporting your data can be customized quite nicely:

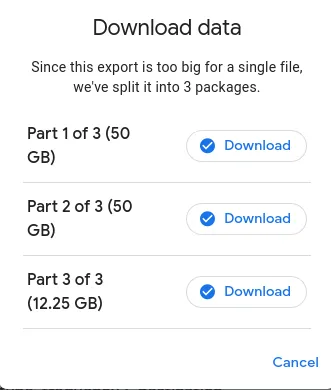

You can select the compression format and archive size. Once you did that, and wait for some nondescript batch-job to complete (that will take several hours), you can download those files:

You can throw that link at wget, as to not to be at the mercy of an X-server if you want to push it to a file server directly (in my case, via ssh).

The resulting files are just zip archives, which you can extract.

christian @ bigiron ➜ GooglePlayMusic lltotal 113G-rw-r--r-- 1 christian christian 51G Feb 23 08:29 takeout-001.zip-rw-r--r-- 1 christian christian 51G Feb 23 08:46 takeout-002.zip-rw-r--r-- 1 christian christian 13G Feb 23 08:50 takeout-003.zipStructure↑

The resulting structure looks like this:

christian @ bigiron ➜ GooglePlayMusic tree -d.└── Takeout └── Google Play Music ├── Playlists │ ├── Dornenreich - In Luft Geritzt.mp3 │ │ └── Tracks │ ├── Ensiferum - Unsung Heroes │ │ └── Tracks │ ├── Metal Mai 2015 │ │ └── Tracks ├── Radio Stations │ └── Recent Stations └── Tracks

53 directoriesI’ve cut out some playlists, but other than that, that’s it. 3 Main folders: Playlists, Radio Stations, and Tracks. On the root of this folder, there lives a archive_browser.html HTML file.

Playlists↑

The playlists folder contains a wild mix of album titles, custom playlists, and generic folders.

Within those folders, taking Austrian Black Metal band Dornenreich’s album “In Luft Geritzt” as an example, you’ll find a bunch of CSV files as such:

christian @ bigiron ➜ Dornenreich - In Luft Geritzt.mp3 lltotal 16K-rw-r--r-- 1 christian christian 90 Feb 22 09:23 Metadata.csvdrwxr-sr-x 3 christian christian 4.0K Feb 23 08:59 .drwxr-sr-x 27 christian christian 4.0K Feb 23 09:38 ..drwxr-sr-x 2 christian christian 4.0K Feb 23 10:13 Trackschristian @ bigiron ➜ Dornenreich - In Luft Geritzt.mp3 ll Trackstotal 128K-rw-r--r-- 1 christian christian 141 Feb 22 09:22 Aufbruch.csv-rw-r--r-- 1 christian christian 138 Feb 22 09:22 'Jagd(1).csv'-rw-r--r-- 1 christian christian 142 Feb 22 09:22 'Aufbruch(2).csv'-rw-r--r-- 1 christian christian 149 Feb 22 09:23 'Flügel In Fels(2).csv'The entire folder doesn’t contain a single music file, just csvs.

christian @ bigiron ➜ Playlists find . -type f -name "*.mp3"These CSVs have the following structure:

christian @ bigiron ➜ Dornenreich - In Luft Geritzt.mp3 cat Tracks/Aufbruch.csvTitle,Album,Artist,Duration (ms),Rating,Play Count,Removed,Playlist Index"Aufbruch","In Luft Geritzt","Dornenreich","292728","0","1","","7"No music thus far. Let’s keep looking.

Radio Stations↑

This one contains a single folder with a bunch of csv files showing me metadata about “recent” radio stations:

christian @ bigiron ➜ Recent Stations cat Dream\ Theater.csvTitle,Artist,Description,Removed,"Other artists on this station","Similar stations""Dream Theater Radio","Dream Theater","Hear songs by Dream Theater, Liquid Tension Experiment, Symphony X, James LaBrie, and more.","","Liquid Tension Experiment, Symphony X, James LaBrie, Jordan Rudess, Mike Portnoy, Steve Vai, Flying Colors, Circus Maximus, Liquid Trio Experiment, Joe Satriani, Pain of Salvation, Yngwie Malmsteen, Andromeda, Shadow Gallery, Kiko Loureiro, Ark, Derek Sherinian, ","The Journey Continues: Modern Prog, Progressive Metal, Instru-Metal, Presenting Iron Maiden, Presenting Rush, Judas Priest's Greatest Riffs, Defenders of the Olde, Reign in Blood, Swords & Sorcery, New Wave of British Heavy Metal, The World of Megadeth, Metal's Ambassadors, Bludgeoning Riffery, The Black Mass, Closer to the Edge: Classic Prog, Rock Me Djently,Not overly helpful and in a broken encoding (text/plain; charset=us-ascii, which causes special characters like apostrophes to be escaped). What more could you ask for?

Tracks↑

The Tracks folder is a monolith of, in my case, 23,529 files. 11,746 are csv files, 11,763 are mp3.

The csv files don’t necessarily correspond to a mp3 (but some do!) and are also not unique:

christian @ bigiron ➜ Tracks cat PaschendalePaschendale\(1\).csv Paschendale\(2\).csv Paschendale.csv# ^ this is zsh auto-completechristian @ bigiron ➜ Tracks cat Paschendale*.csvTitle,Album,Artist,Duration (ms),Rating,Play Count,Removed"Paschendale","Dance of Death","Iron Maiden","507123","0","0",""Title,Album,Artist,Duration (ms),Rating,Play Count,Removed"Paschendale","From Fear To Eternity The Best Of 1990-2010 [Disc 1]","Iron Maiden","507123","0","0",""Title,Album,Artist,Duration (ms),Rating,Play Count,Removed"Paschendale","Death On The Road [Live] [Disc 1]","Iron Maiden","617465","0","0",""Delightful - Paschendale (0) through (2) as a CSV file, but not actual music.

When it comes to the actual music files, it appears that they do contain id3v2 tags:

christian @ bigiron ➜ Tracks id3v2 -l 'Dornenreich - Flammentriebe - Flammenmensch.mp3'id3v2 tag info for Dornenreich - Flammentriebe - Flammenmensch.mp3:TIT2 (Title/songname/content description): FlammenmenschTPE1 (Lead performer(s)/Soloist(s)): DornenreichTPE2 (Band/orchestra/accompaniment): DornenreichTALB (Album/Movie/Show title): FlammentriebeTYER (Year): 2011TRCK (Track number/Position in set): 1/8TPOS (Part of a set): 1/1TCON (Content type): Black Metal (138)APIC (Attached picture): ()[, 3]: image/jpeg, 14297 bytesPRIV (Private frame): (unimplemented)Dornenreich - Flammentriebe - Flammenmensch.mp3: No ID3v1 tagarchive_browser.html↑

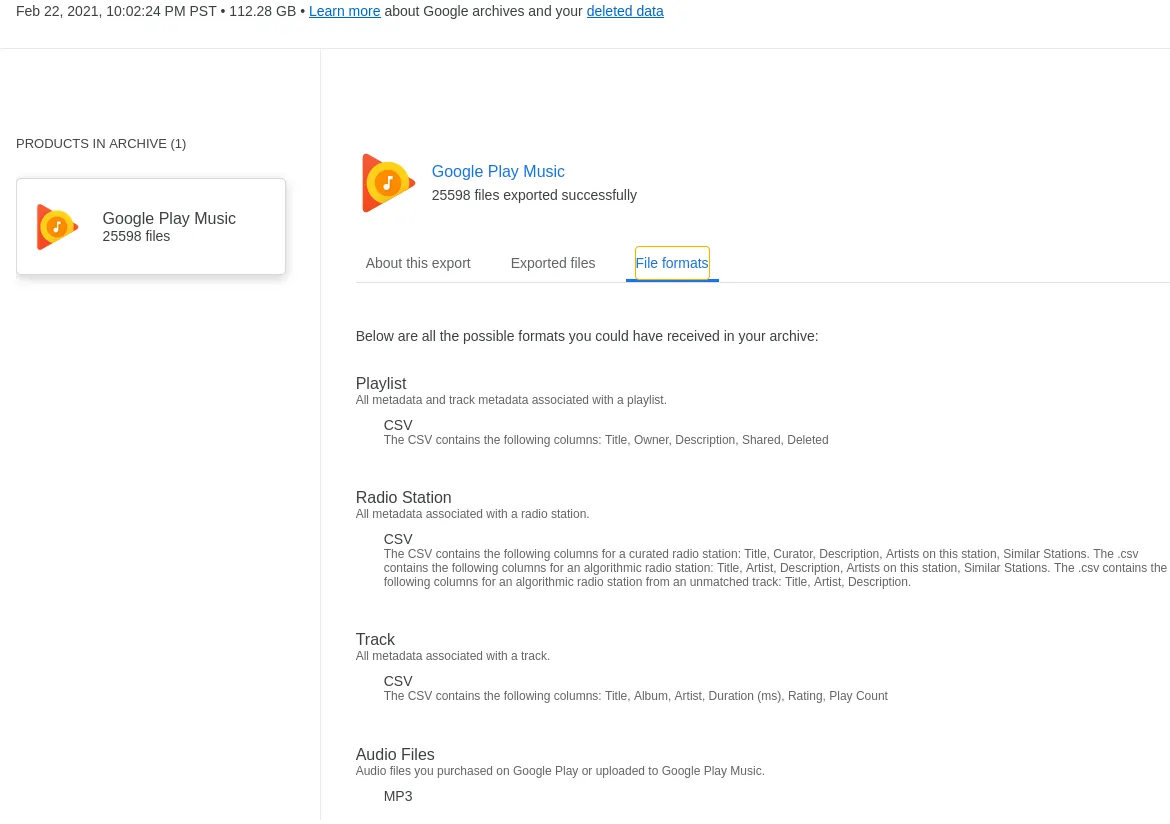

I’ve pointed a local Apache web server at that file and we can find a rough description of the exported data:

Which is not overly helpful, but gives us rough data dictionaries for all CSV files.

What we have so far↑

We now somewhat understand what’s going on here - the export contains all mp3 files that were uploaded (as a backup) at one point. Music files that were never uploaded and just streamed - or not exported, for some reason - will show up as csv files.

There are duplicates and there are no naming conventions kept (e.g. $ARTIST/$ALBUM/$INDEX-$TRACK).

We also now that the data doesn’t contain any form of keys or indexes, meaning we won’t have anything to uniquely match for instance band or album names.

Last but not least, file na,es contain spaces and special characters, which aren’t great for use in e.g. bash.

To summarize:

- Some files exists as

mp3, others only asmetadata/csv - Naming conventions are non-existent

- There are duplicates

- The

csvs are not consistently encoded asutf-8 - There are no keys to match to other data

- The

mp3s have someid3v2tags - File names are not in a

UNIXstyle, i.e. contain spaces

The End-Goal: Organization↑

With this out of the way, let’s see what we can do with this.

I already maintain my music, a more recent copy, in the format mentioned above, i.e. $ARTIST/$ALBUM/$INDEX-$TRACK, with id3v2 tags on all files, for instance -

christian @ bigiron ➜ cd $MUSIC/Dornenreich/Flammentriebechristian @ bigiron ➜ Flammentriebe id3v2 -l 01\ Flammenmensch.mp3id3v1 tag info for 01 Flammenmensch.mp3:Title : Flammenmensch Artist: DornenreichAlbum : Flammentriebe Year: 2011, Genre: Black Metal (138)Comment: Track: 1id3v2 tag info for 01 Flammenmensch.mp3:TIT2 (Title/songname/content description): FlammenmenschTPE1 (Lead performer(s)/Soloist(s)): DornenreichTRCK (Track number/Position in set): 1/8TALB (Album/Movie/Show title): FlammentriebeTPOS (Part of a set): 1/1TCON (Content type): Black Metal (138)TMED (Media type): CDIf we were able to…

- Re-organize all files into a logical naming convention

- Remove all duplicates, keeping only the “best” copy (based on compression/quality)

- Match them with the master data copy of music on my server and add all that are missing to it

- Match all non-existent mp3 files to the master data copy of music, and call out all that are missing

In order to achieve this, let’s pretend this is not a weekend during COVID, but rather a professional Data Engineering project - and over-engineer the hell out of it. For fun. And out of desparation.

Step 1: Build an Architecture↑

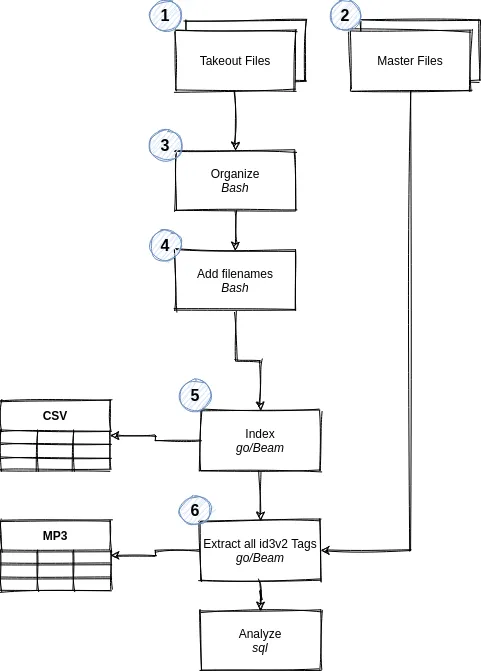

First, we’ll design a quick architecture that uses proven tools - we don’t need a lot, as we’re really only trying to parse and move around 100GB around.

- Takeout files are our incoming data

- Master files are our existing library

- Organize will simply move

csvandmp3files into their own respective directories - Add filenames will add filenames to the

csvs (see below) - Index will move all

csvfiles, i.e. structured data, to tables - Extract id3v2 will extract the unstructured data’s

id3v2tags - Analyze will be the

sqlportion of the exercise, where we try to make sense of our data

When it comes to technology, I’ll be using bash for scripting, go with Apache Beam for more intense workloads, and MariaDB for a quick-and-easy database that can handle the number of records we can expect. Plus I have one running on my server anyways.

Step 2: Provisioning a “Dev Environment”↑

Since we’re at it, we might as well grab a representative set of data in a test environment. For this, I simply created local folders on a different drive-array and copied some data:

mkdir -p "$DEV_ENV/GooglePlayMusic/Takeout/Google Play Music/"cp -r "$PROD_ENV/GooglePlayMusic/Takeout/Google Play Music/Radio\ Stations" "$DEV_ENV/GooglePlayMusic/Takeout/Google Play Music/"cp -r "$PROD_ENV/GooglePlayMusic/Takeout/Google Play Music/Playlists" "$DEV_ENV/GooglePlayMusic/Takeout/Google Play Music/"find "/mnt/6TB/Downloads/GooglePlayMusic/Takeout/Google Play Music/Tracks/" -maxdepth 1 -type f | shuf | head -1000 > /tmp/sample.txtwhile read l; do cp "${l}" "/mnt/1TB/Dev/GooglePlayMusic/Takeout/Google Play Music/Tracks/"; done < /tmp/sample.txtThe last lines is the only funky one and simply copies 1,000 random files from the “Tracks” directory. I find it a good idea to pipe to an output file for deterministic behavior’s sake, rather than piping directly to xargs and cp. xargs would be much faster, though.

Step 3: Re-Organizing files↑

The first step for any data project (besides figuring out what you’re trying to do) should be to get an understanding of the data we’re working with. We’ve already made the first steps by going through that >100GB dump above, but formalizing it will help us to truly understand what’s going on and to ensure we can script out everything without missing corner cases.

Given that our input file structure is all over the place (with >20,000 mixed-type files in one directory!), we can script that out to make it a repeatable process.

One word of advice here - even if you think you’ll never use the script again and you’re the only person ever using it, just assume that to be wrong and that somebody in your organization will have to use it at a later point.

This is why we woefully over-engineer this thing - argument parsing, escaping Strings, all that - because chances are, you’ll see it pop up soon. This comes from a decent amount of experience - I find scripts I wrote for myself ages ago in the wild way too often.

#!/bin/bash

# Exit on errorset -e

POSITIONAL=()while [[ $# > 0 ]]; do case "$1" in -b|--base-dir) BASE_DIR="${2}" shift 2 ;; -t|--target-dir) TARGET_DIR="${2}" shift 2 ;; *) POSITIONAL+=("$1") shift ;; esacdone

set -- "${POSITIONAL[@]}"

# Check argsif [[ -z "${BASE_DIR}" || -z "${TARGET_DIR}" ]]; then echo "Usage: organize.sh --base-dir \$PATH_TO_EXPORT --target_dir \$PATH_TO_OUTPUT" exit 1fi

# Set base foldersTRACK_FOLDER="${BASE_DIR}/Tracks"PLAYLISTS_FOLDER="${BASE_DIR}/Playlists"RADIO_FOLDER="${BASE_DIR}/Radio Stations"

# Check folderif [[ ! -d "${TRACK_FOLDER}" || ! -d "${PLAYLISTS_FOLDER}" || ! -d "${RADIO_FOLDER}" ]]; then echo "--base-dir must point to the folder containing /Tracks, /Playlists, and /Radio\ Stations" exit 1fi

# Define targetsecho "Creating target dirs in $TARGET_DIR..."mkdir -p "${TARGET_DIR}"CSV_TARGET="${TARGET_DIR}/csv/"MP3_TARGET="${TARGET_DIR}/mp3/"PLAYLIST_TARGET="${TARGET_DIR}/playlists/"RADIO_TARGET="${TARGET_DIR}/radios/"

# Create structure for CSVs and MP3smkdir -p "${CSV_TARGET}"mkdir -p "${MP3_TARGET}"mkdir -p "${PLAYLIST_TARGET}"mkdir -p "${RADIO_TARGET}"

# Copy flat files filesecho "Copying files from $TRACK_FOLDER..."find "${TRACK_FOLDER}" -type f -iname "*.csv" -exec cp -- "{}" "${CSV_TARGET}" \;find "${TRACK_FOLDER}" -type f -iname "*.mp3" -exec cp -- "{}" "${MP3_TARGET}" \;

# Playlists need to be concatenatedecho "Copying files from $PLAYLISTS_FOLDER..."find "${PLAYLISTS_FOLDER}" -type f -mmin +1 -print0 | while IFS="" read -r -d "" f; do # Ignore summaries if [[ ! -z $(echo "${f}" | grep "Tracks/" ) ]]; then # Group playlistName="$(basename "$(dirname "$(dirname "${f}")")")" targetCsv="${PLAYLIST_TARGET}/$playlistName.csv" touch "${targetCsv}" echo "Working on playlist $playlistName to $targetCsv" # Add header if [[ -z $(cat "${targetCsv}" | grep "Title,Album,Artist") ]]; then echo "Title,Album,Artist,Duration (ms),Rating,Play Count,Removed,Playlist Index" > "${targetCsv}" fi echo "$(tail -n +2 "${f}")" >> "${targetCsv}" fidone

# Just flat file copyecho "Copying files from $RADIO_TARGET..."find "${RADIO_FOLDER}" -type f -exec cp -- "{}" "${RADIO_TARGET}" \;The script should be decently self-explanatory - it copies data into a new, flat structure. We do some pseudo-grouping to concatenate all Playlists into single CSVs. Please note that this is all single-threaded, which I don’t recommend - with nohup and the like, you can trivially parallelize this.

Once we run it, we get a nice and clean structure:

christian @ bigiron ➜ ./organize.sh --base-dir "$DEV_ENV" --target-dir ./clean/christian @ bigiron ➜ clean tree -d ..├── csv├── mp3├── playlists└── radioschristian @ bigiron ➜ clean du -h --max-depth=1 .2.1M ./csv4.7G ./mp35.1M ./playlists4.0K ./radios4.7GThis dataset will be our starting point. In real data pipelines, it is not uncommon to do some basic cleanup before starting the real work - just because it makes our lives so much easier down the line.

Step 4: Creating Data Dictionaries↑

Based on our initial cleanup, we can now automatically profile our csv files, given that we have all of them in one place.

Python and pandas are great tools to have at hand for that -

import pandas as pdimport globimport argparse

if __name__ == '__main__': parser = argparse.ArgumentParser() parser.add_argument('-i', '--in_dir', type=str, required=True, help='Input directory') args = parser.parse_args()

df = pd.concat((pd.read_csv(f) for f in glob.glob(args.in_dir))) print(f'Schema for %s is:', in_dir) print(df.info(show_counts=True))Which gives us outputs like this:

<class 'pandas.core.frame.DataFrame'>Int64Index: 1283 entries, 0 to 0Data columns (total 8 columns): # Column Non-Null Count Dtype--- ------ -------------- ----- 0 Title 1283 non-null object 1 Album 1283 non-null object 2 Artist 1283 non-null object 3 Duration (ms) 1283 non-null int64 4 Rating 1283 non-null int64 5 Play Count 1283 non-null int64 6 Removed 0 non-null float64 7 Playlist Index 1283 non-null int64dtypes: float64(1), int64(4), object(3)memory usage: 90.2+ KBWhich we can use to build out our tables:

| Table | Column | Type |

|---|---|---|

| Playlist | Title | STRING |

| Playlist | Album | STRING |

| Playlist | Artist | STRING |

| Playlist | Duration (ms) | INTEGER |

| Playlist | Rating | INTEGER |

| Playlist | Play Count | INTEGER |

| Playlist | Removed | FLOAT |

| Playlist | Playlist Index | INTEGER |

| Table | Column | Type |

|---|---|---|

| Song | Title | STRING |

| Song | Album | STRING |

| Song | Artist | STRING |

| Song | Duration (ms) | INTEGER |

| Song | Rating | INTEGER |

| Song | Play Count | INTEGER |

| Song | Removed | FLOAT |

| Table | Column | Type |

|---|---|---|

| Radio | Title | STRING |

| Radio | Artist | STRING |

| Radio | Description | STRING |

| Radio | Removed | FLOAT |

| Radio | Other artists on this station | STRING |

| Radio | Similar stations | STRING |

| Radio | Artists on this station | STRING |

These data dictionaries and table definitions will help us to understand the structure of the data. Documentation is boring, yes, but critically important for any data project.

Note that the floats here aren’t really that - they are binary indicators well change later. float is the pandas default, I believe.

Step 5: Building a Database Schema↑

We can now turn those data dictionaries into simple MariaDB tables, by just abiding to the SQL engine’s naming conventions and restrictions.

Our schema should, at the very least, do the following:

- Contain all the data we have without loss

- Contain data that is close, but not necessarily identical, to the raw data

- Abide to semi-useful naming conventions

For instance, for our Song csvs, we might want something like this:

CREATE DATABASE IF NOT EXISTS `googleplay_raw`;

CREATE OR REPLACE TABLE `googleplay_raw`.`song` ( `title` TEXT, `album` TEXT, `artist` TEXT, `duration_ms` INTEGER, `rating` INTEGER, `play_count` INTEGER, `removed` FLOAT, `file_name` TEXT);All names are clear, have a clear data type, and contain all data we have.

Step 6: Indexing all Metadata↑

Now to the fun part: Actually touching the data. You might have realized that until now (apart from some profiling), we haven’t even bothered to really read any data.

We’ll be using Apache Beam for it and because I hate myself, we’ll be writing it in go.

Beam is useful in the sense that we can relatively quickly build a pipeline, using pre-built PTransforms, rather than having to manage separate goroutines, deal with channels, deal with custom IO - in short, it would, in theory, be a fast and easy way to process the CSV files.

You might have noticed that we’ve added one field - file_name - in the previous section. Now, since we’ll be using Apache Beam in the next step, there’s 2 schools of thought: Force Beam to provide the PCollection’s file name (that is not something you can easily do, given the way their SplittableDoFns work) or manipulate your input data to provide this information.

We’ll do the latter. So, bash to the rescue, once again:

#!/bin/bash

# Exit on errorset -e

POSITIONAL=()while [[ $# > 0 ]]; do case "$1" in -b|--base-dir) BASE_DIR="${2}" shift 2 ;; *) POSITIONAL+=("$1") shift ;; esacdone

set -- "${POSITIONAL[@]}"

# Check argsif [[ -z "${BASE_DIR}" ]]; then echo "Usage: add_filename_to_csv.sh --base-dir \$PATH_TO_EXPORT" exit 1fi

find "${BASE_DIR}" -type f -name "*.csv" -print0 | while IFS= read -r -d '' f; do echo "" > /tmp/out.csv bname=$(basename "${f}") echo "Adding $bname to $f" ix=0

while read l; do if [[ $ix -eq 0 ]]; then echo "${l},file_name" >> /tmp/out.csv else echo "${l},${bname}" >> /tmp/out.csv fi ix=$(($ix + 1)) done < "$f" IFS=$OLDIFS if [[ $ix -ne 0 ]]; then cat "/tmp/out.csv" > "${f}" else echo "File $f is empty" fidoneNote the re-using of IFS, the Internal Field Separator, here. This is why you don’t use spaces in file names.

This script turns:

cat clean/csv/Loki\ God\ of\ Fire.csvTitle,Album,Artist,Duration (ms),Rating,Play Count,Removed"Loki God of Fire","Gods of War","Manowar","230016","0","1",""Into

Title,Album,Artist,Duration (ms),Rating,Play Count,Removed,file_name"Loki God of Fire","Gods of War","Manowar","230016","0","1","","Loki God of Fire.csv"And we can use this data to create a pipline.

import (//..

"github.com/apache/beam/sdks/go/pkg/beam"// ..)

type Song struct { Title string `column:"title"` Album string `column:"album"` Artist string `column:"artist"` // ..}

func (s Song) getCols() []string { return []string{"title", "album", "artist", "duration_ms", "rating", "play_count", "removed", "file_name"}}

func (f *Song) ProcessElement(w string, emit func(Song)) { data := strings.Split(w, ",") //..

// Filter non-null fields if data[0] != "" { fmt.Printf("Song: %v\n", s) emit(*s) }}

func main() {//.. beam.Init() p := beam.NewPipeline() s := p.Root() // Build pipeline lines := textio.Read(s, *trackCsvDir) songs := beam.ParDo(s, &Song{}, lines) // Write to DB databaseio.Write(s, "mysql", conStr, "song", Song{}.getCols(), songs)

// Run until we find errors if err := beamx.Run(context.Background(), p); err != nil { log.Fatalf("Failed to execute job: %v", err) }}This pipeline would read all our Song csv files and write it to our Songs table. It uses the TextIO ParDo to read each CSV, custom ParDos to map the data to structs to map our table, and writes it to it.

That being said, the Beam documentation remains rather… sparse. [1]

func Write(s beam.Scope, driver, dsn, table string, columns []string, col beam.PCollection)Write writes the elements of the given

PCollection<T>to database, if columns left empty all table columns are used to insert into, otherwise selectedhttps://pkg.go.dev/github.com/apache/beam/sdks/go/pkg/beam/io/databaseio#Write

O… okay. PCollection<T> is my favorite. go doesn’t have generics. At least not yet - ETA for generics in go is end of this year (<T> is Java/Scala for “PCollection of Type T”). Yes, yes - if you actually read the source, you’ll quickly find some interesting uses of Reflect to build some bastardized generics-type structure, but my point remains - Beam’s (and by proxy, Google’s Dataflow documentation) leaves a lot to be desired.

For instance, this error:

8: ParDo[beam.createFn] Out:[7] caused by: creating row mapperfailed to matched a main.Song field for SQL column: titleexit status 1(Source)

Was ultimately caused by not exporting (which, in go, is done by using an uppercase character to start a struct field) and aliasing the struct fields:

type Song struct { Title string `column:"title"` Album string `column:"album"` Artist string `column:"artist"` Duration_ms int `column:"duration_ms"` Rating int `column:"rating"` Play_count int `column:"play_count"` Removed int `column:"removed"`}Don’t ever believe that this is documented anywhere. I found the mapping in their unit tests.

But, in any case, the pipeline above creates records as such:

We can simply extend this to also cover all three other CSV files, using the same logic and clean it up a bit.

Note: The code on GitHub uses a utils.go module, so we avoid copy-paste code

package main

import ( "context" "flag" "fmt" "log" "strconv"

"github.com/apache/beam/sdks/go/pkg/beam" "github.com/apache/beam/sdks/go/pkg/beam/io/databaseio" "github.com/apache/beam/sdks/go/pkg/beam/io/textio" "github.com/apache/beam/sdks/go/pkg/beam/x/beamx" _ "github.com/go-sql-driver/mysql")

var ( trackCsvDir = flag.String("track_csv_dir", "", "Directory containing all track CSVs") playlistsCsvDir = flag.String("playlist_csv_dir", "", "Directory containing all playlist CSVs") radioCsvDir = flag.String("radio_csv_dir", "", "Directory containing all radio CSVs") databaseHost = flag.String("database_host", "localhost", "Database host") databaseUser = flag.String("database_user", "", "Database user") databasePassword = flag.String("database_password", "", "Database password") database = flag.String("database", "googleplay_raw", "Database name"))

type Playlist struct { Title string `column:"title"` Album string `column:"album"` Artist string `column:"artist"` Duration_ms int `column:"duration_ms"` Rating int `column:"rating"` Play_count int `column:"play_count"` Removed bool `column:"removed"` PlaylistIndex int `column:"playlist_ix"`}

func (s Playlist) getCols() []string { return []string{"title", "album", "artist", "duration_ms", "rating", "play_count", "removed", "playlist_ix"}}

func (f *Playlist) ProcessElement(w string, emit func(Playlist)) { data, err := PrepCsv(w) if err != nil { return } duration_ms, _ := strconv.Atoi(GetOrDefault(data, 3)) rating, _ := strconv.Atoi(GetOrDefault(data, 4)) playCount, _ := strconv.Atoi(GetOrDefault(data, 5)) playlist_ix, _ := strconv.Atoi(GetOrDefault(data, 7))

s := &Playlist{ Title: GetOrDefault(data, 0), Album: GetOrDefault(data, 1), Artist: GetOrDefault(data, 2), Duration_ms: duration_ms, Rating: rating, Play_count: playCount, Removed: ParseRemoved(data, 6), PlaylistIndex: playlist_ix, }

fmt.Printf("Playlist: %v\n", s) emit(*s)}

type Song struct { Title string `column:"title"` Album string `column:"album"` Artist string `column:"artist"` Duration_ms int `column:"duration_ms"` Rating int `column:"rating"` Play_count int `column:"play_count"` Removed bool `column:"removed"` FileName string `column:"file_name"`}

func (s Song) getCols() []string { return []string{"title", "album", "artist", "duration_ms", "rating", "play_count", "removed", "file_name"}}

func (f *Song) ProcessElement(w string, emit func(Song)) { data, err := PrepCsv(w) if err != nil { return } duration_ms, _ := strconv.Atoi(GetOrDefault(data, 3)) rating, _ := strconv.Atoi(GetOrDefault(data, 4)) playCount, _ := strconv.Atoi(GetOrDefault(data, 5))

s := &Song{ Title: GetOrDefault(data, 0), Album: GetOrDefault(data, 1), Artist: GetOrDefault(data, 2), Duration_ms: duration_ms, Rating: rating, Play_count: playCount, Removed: ParseRemoved(data, 6), FileName: GetOrDefault(data, 7), }

fmt.Printf("Song: %v\n", s) emit(*s)}

type Radio struct { Title string `column:"title"` Artist string `column:"artist"` Description string `column:"description"` Removed bool `column:"removed"` Similar_stations string `column:"similar_stations"` Artists_on_this_station string `column:"artists_on_this_station"`}

func (s Radio) getCols() []string { return []string{"title", "artist", "description", "removed", "similar_stations", "artists_on_this_station"}}

func (f *Radio) ProcessElement(w string, emit func(Radio)) { data, err := PrepCsv(w) if err != nil { return }

s := &Radio{ Title: GetOrDefault(data, 0), Artist: GetOrDefault(data, 1), Description: GetOrDefault(data, 2), Removed: ParseRemoved(data, 3), Similar_stations: GetOrDefault(data, 4), Artists_on_this_station: GetOrDefault(data, 5), }

fmt.Printf("Radio: %v\n", s) emit(*s)}

func process(s beam.Scope, t interface{}, cols []string, inDir, dsn, table string) { // Read lines := textio.Read(s, inDir) data := beam.ParDo(s, t, lines) // Write to DB databaseio.Write(s, "mysql", dsn, table, cols, data)}

func main() { // Check flags flag.Parse() if *trackCsvDir == "" || *playlistsCsvDir == "" || *radioCsvDir == "" || *databasePassword == "" { log.Fatalf("Usage: index_match --track-csv_dir=$TRACK_DIR --playlist_csv_dir=$PLAYLIST_DIR --radio_csv_dir=$RADIO_DIR--database_password=$PW [--database_host=$HOST --database_user=$USER]") } dsn := fmt.Sprintf("%v:%v@tcp(%v:3306)/%v", *databaseUser, *databasePassword, *databaseHost, *database) fmt.Printf("dsn: %v\n", dsn) fmt.Printf("cols: %v\n", Song{}.getCols()) // Initialize Beam beam.Init() p := beam.NewPipeline() s := p.Root() // Songs process(s, &Song{}, Song{}.getCols(), *trackCsvDir, dsn, "song") // Radio process(s, &Radio{}, Radio{}.getCols(), *radioCsvDir, dsn, "radio") // Playlists process(s, &Playlist{}, Playlist{}.getCols(), *playlistsCsvDir, dsn, "playlists") // Run until we find errors if err := beamx.Run(context.Background(), p); err != nil { log.Fatalf("Failed to execute job: %v", err) }}In case this seems confusing, please take a look at an older article I wrote on the topic.

Once done, let’s run the pipeline as such:

export GOLANG_PROTOBUF_REGISTRATION_CONFLICT=ignore

go get github.com/go-sql-driver/mysqlgo get -u github.com/apache/beam/sdks/go/...

PW=passwordDB_USER=takeoutDB_HOST=bigirion.local

go run 03-beam-csv-to-sql.go \ --track_csv_dir="$(pwd)/test_data/clean/csv/*.csv" \ --playlist_csv_dir="$(pwd)/test_data/clean/playlists/*.csv" \ --radio_csv_dir="$(pwd)/test_data/clean/radios/*.csv" \ --database_host=$DB_HOST \ --database_user=$DB_USER \ --database_password="${PW}"[1] Indeed, I should raise a PR for it

Step 7: Indexing all non-structured data↑

What you will notice, however, is that we are thus far only touching the csv files, not the mp3s.

Here, once again, multiple schools of thought are at play: Do you combine pipelines for structured and unstructured data or do you keep them separate?

Now naturally, this all depends on your project and environment; genereally speaking, I am a big fan of separation of duties for jobs and on relying on shared codebases - libraries, modules and the like - do implement specific functions that might share common attributes.

This provides several benefits during operations - jobs operating on separate data sources can be updated, scaled, and maintained independently (which is why the previous job should really have a flag that runs a single type of source data per instance!), while still having the chance to be customized to truly fit a specific use case.

For unstructured data, Apache Beam tends not the be the right tool, given the Beam usually operates on the splittable elements of files, e.g. lines in a csv files or records in avro files. You can absolutely do it, but as I’ve mentionend above, I do not believe there to be anything wrong with structured data preparation prior to your core pipelines.

With that being said, we’ll simply sent metadata to another Beam pipeline, by providing a list of all MP3 files and their corresponding path:

find $(pwd)/clean/mp3 -type f -name "*.mp3" > all_mp3.txtWith this approach, we can actually re-use our Beam pipeline, as we now use it to maintain metadata and references towards unstructured files, without actually touching them. In this case, I have written a separate pipeline for easier presentation.

When it comes to writing it, we can use bogem/id3v2, an id3v2 library for go.

id3v2, however, the standard is not exactly perfect to work with - all tags, similar to EXIF on images, are entirely optional and depend on somebody, well, adding them to the file - that is not always a given with CD rips or even digital downloads, which you often get from vinyl purchases.

Hence, we’ll focus on some basic tags:

type Id3Data struct { Artist string `column:"artist"` // TPE1 Title string `column:"title"` // TIT2 Album string `column:"album"` // TALB Year int `column:"year"` // TYER Genre string `column:"genre"` // TCON TrackPos int `column:"trackPos"` // TRCK TrackMax int `column:"maxTrackPos"` PartOfSet string `column:"partOfSet"` // TPOS FileName string `column:"file_name"` FullPath string `column:"full_path"` //Other string}Which gives us this pipeline:

package main

// go get -u github.com/bogem/id3v2

import ( "context" "flag" "fmt" "log" "path/filepath" "strconv" "strings"

"github.com/apache/beam/sdks/go/pkg/beam" "github.com/apache/beam/sdks/go/pkg/beam/io/databaseio" "github.com/apache/beam/sdks/go/pkg/beam/io/textio" "github.com/apache/beam/sdks/go/pkg/beam/x/beamx" "github.com/bogem/id3v2"

_ "github.com/go-sql-driver/mysql")

var ( mp3File = flag.String("mp3_list", "", "File containing all Mp3 files") databaseHost = flag.String("database_host", "localhost", "Database host") databaseUser = flag.String("database_user", "", "Database user") databasePassword = flag.String("database_password", "", "Database password") database = flag.String("database", "googleplay_raw", "Database name"))

type Id3Data struct { Artist string `column:"artist"` // TPE1 Title string `column:"title"` // TIT2 Album string `column:"album"` // TALB Year int `column:"year"` // TYER Genre string `column:"genre"` // TCON TrackPos int `column:"trackPos"` // TRCK TrackMax int `column:"maxTrackPos"` PartOfSet string `column:"partOfSet"` // TPOS FileName string `column:"file_name"` FullPath string `column:"full_path"` //Other string}

func (s Id3Data) getCols() []string { return []string{"artist", "title", "album", "year", "genre", "trackPos", "maxTrackPos", "partOfSet", "file_name", "full_path"}}

func convTrackpos(pos string) (int, int) { if pos != "" { data := strings.Split(pos, "/") fmt.Println(data) if len(data) > 1 { trck, err1 := strconv.Atoi(data[0]) mtrck, err2 := strconv.Atoi(data[1]) if err1 == nil && err2 == nil { return trck, mtrck } } else if len(data) == 1 { trck, err := strconv.Atoi(data[0]) if err == nil { return trck, -1 } } } return -1, -1}

func getAllTags(tag id3v2.Tag) []string { all := tag.AllFrames() keys := make([]string, len(all))

i := 0 for k := range all { // Skip APIC, PRIV (album image binary) if k != "APIC" { keys[i] = k }

i++ }

for i := range keys { fmt.Printf("%v: %v\n", keys[i], tag.GetTextFrame(keys[i])) } return keys}

func parseMp3ToTags(path string) (Id3Data, error) { tag, err := id3v2.Open(path, id3v2.Options{Parse: true}) if err != nil { return Id3Data{}, err } defer tag.Close() //getAllTags(*tag) year, _ := strconv.Atoi(tag.GetTextFrame("TYER").Text) tpos, mpos := convTrackpos(tag.GetTextFrame("TRCK").Text) return Id3Data{ Artist: tag.GetTextFrame("TPE1").Text, Title: tag.GetTextFrame("TIT2").Text, Album: tag.GetTextFrame("TALB").Text, Genre: tag.GetTextFrame("TCON").Text, Year: year, TrackPos: tpos, TrackMax: mpos, PartOfSet: tag.GetTextFrame("TPOS").Text, FileName: filepath.Base(path), FullPath: path, //Other: getAllTags(tag), }, nil}

func (f *Id3Data) ProcessElement(path string, emit func(Id3Data)) { data, err := parseMp3ToTags(path) if err != nil { fmt.Printf("Error: %\n", err) return } emit(data)}

func process(s beam.Scope, t interface{}, cols []string, inDir, dsn, table string) { // Read lines := textio.Read(s, inDir) data := beam.ParDo(s, t, lines) // Write to DB databaseio.Write(s, "mysql", dsn, table, cols, data)}

func main() { flag.Parse() if *mp3File == "" || *databasePassword == "" { log.Fatalf("Usage: extract_id3v2 --mp3_list=$TRACK_DIR --database_password=$PW [--database_host=$HOST --database_user=$USER]") } dsn := fmt.Sprintf("%v:%v@tcp(%v:3306)/%v", *databaseUser, *databasePassword, *databaseHost, *database)

// Initialize Beam beam.Init() p := beam.NewPipeline() s := p.Root() process(s, &Id3Data{}, Id3Data{}.getCols(), *mp3File, dsn, "id3v2") // Run until we find errors if err := beamx.Run(context.Background(), p); err != nil { log.Fatalf("Failed to execute job: %v", err) }}Step 8: Running all pipelines↑

First, csv_to_sql:

2021/02/27 11:38:37 written 511 row(s) into song2021/02/27 11:38:37 written 15 row(s) into radio2021/02/27 11:38:37 written 1982 row(s) into playlists1.57s user 0.25s system 135% cpu 1.336 totalFollowed by

First, csv_to_sql:

2021/02/27 11:40:16 written 493 row(s) into id3v21.54s user 0.23s system 135% cpu 1.309 totalAnd naturally, we’ll need to run extract_id3v2 against the master list of music as well, another ~120GB:

find $(pwd)/Music -type f -name "*.mp3" > all_mp3_master.txtgo run extract_id3v2.go utils.go \ --mp3_list="$(pwd)/all_mp3_master.txt" \ --database_host=$DB_HOST \ --database_user=$DB_USER \ --database_password="${PW}" \ --database=googleplay_master | grep "unsupported version of ID3" >> unsup.txt2021/02/27 12:25:09 written 8668 row(s) into id3v2go run extract_id3v2.go utils.go --mp3_list="$(pwd)/all_mp3_master.txt" 5.45s user 1.16s system 92% cpu 7.115 totalHere, unforunately, we find ourselves in a bit of a pickle - the library we’re using does not support ID3v2.2, only 2.3+. Rather than making this article even longer, I’ve simply piped out the broken records separately, knowing that we need to ignore them. About ~2,100 files are affected.

Step 9: Matching↑

Now that we have all data on a sql database, we can start matching.

Note how we didn’t normalize our fields, for instance -

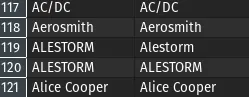

SELECT s.artist AS csv_arist, i.artist AS mp3_artistFROM googleplay_raw.song AS sLEFT OUTER JOIN googleplay_raw.id3v2 AS iON LOWER(i.artist) = LOWER(s.artist)ORDER BY i.artist ASCGives us matches, but not exact ones:

Again, another philosophical point - we loaded raw data into a format we can query and analyze. We did not clean it up, as to not alter the raw data, short of changing the encoding. There are points to be made to replicate this dataset now and provide a cleaned or processed dataset, but I’ll be skipping that in the interest of time. We’ll do it live using sql.

So, let’s first see if there are csv files that point to mp3s that already exist.

SELECT s.artist AS csv_arist ,i.artist AS mp3_artist ,s.album AS csv_album ,i.album AS mp3_album ,s.title AS csv_title ,i.title AS mp3_title ,s.file_nameFROM googleplay_raw.song AS sLEFT OUTER JOIN googleplay_raw.id3v2 AS iON ( TRIM(LOWER(i.artist)) = TRIM(LOWER(s.artist)) AND TRIM(LOWER(i.album)) = TRIM(LOWER(s.album)) AND TRIM(LOWER(i.title)) = TRIM(LOWER(s.title)) )WHERE i.artist IS NOT NULLORDER BY i.artist ASCAnd indeed, we get matches!

christian @ bigiron ➜ Dev ll clean/csv/Bite\ the\ Hand.csv-rw-r--r-- 1 christian christian 146 Feb 27 11:04 'clean/csv/Bite the Hand.csv'christian @ bigiron ➜ Dev ll clean/mp3/Megadeth\ -\ Endgame\ -\ Bite\ the\ Hand.mp3-rw-r--r-- 1 christian christian 9.3M Feb 27 08:50 'clean/mp3/Megadeth - Endgame - Bite the Hand.mp3'So we already know to ignore those records.

Let’s try to find records that have been added through the export, i.e. don’t exist in our master list yet:

SELECT iv2.artist, iv2.album, iv2.title, iv2.full_pathFROM googleplay_master.id3v2 AS iv2WHERE NOT EXISTS ( SELECT iv.artist, iv.album, iv.title FROM googleplay_raw.id3v2 iv)And I am glad to report that the answer to this query is: All records exist already (for both “Dev” and the whole data set). The export, being an old backup, is a subset of the music stored in the server, even though the files are named differently. :)

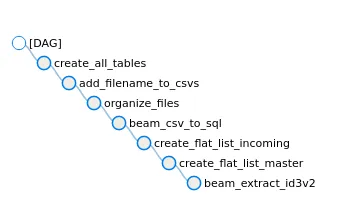

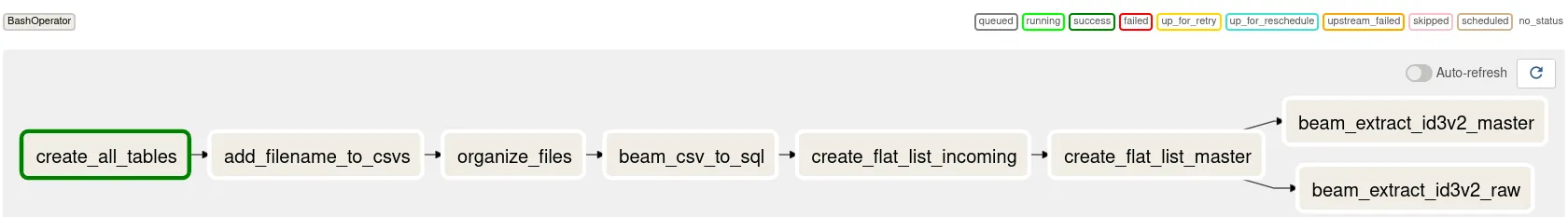

Step 9: Orchestration↑

Assuming all previous steps ran on the test data, let’s orchestrate this pipeline, with all its components, using Apache Airflow.

Airflow uses Python to build out pipelines to orchestrate steps, and if you care for details, take a look at the GitHub repository.

Or as Graph:

I will happily admit that my Airflow knowledge has been outdated since ca. 2017, so please keep that in mind while reading this DAG. The pipeline is rather simple and just runs all steps as Bash steps sequentially (except for the last 2) - it’s essentially a glorified shell script, but you can, of course, make it “production ready” by spending more time on it. Airflow is also available on Google Cloud as Cloud Composer, which is pretty neat.

Next Steps↑

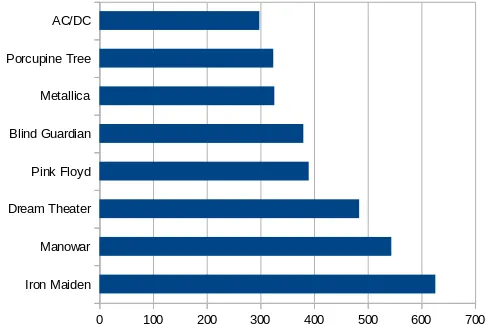

Now we have all music, both Takeout and existing data, organized in a nice, performant SQL environment. Nothing is stopping us from running more analytics, visualizing the data, or using it as a baseline for a homegrown Discogs-type alternative. We should probably also de-duplicate the data.

For instance, here’s the top mentions of bands across tables in the export for me:

Which seems about right.

Naturally, we are also somewhat ignoring non-mp3 files, such as flac or m4as, but that is a story for another time. We would have to tackle pipelines for each type, which I won’t do for this article.

Conclusion↑

Well this was a giant waste of time again - I thoroughly enjoyed it.

What we essentially did was play pretend and used a fairly standard Data Engineering toolset to tackle some real-world, bad data.

We’ve used tools many Data Engineers will be familiar with - Python, Apache Beam, Airflow, SQL, csv files - but also some maybe more obscure things, such as go and using unstructured files. I’ve semi-seriously made a point for using go instead of Rust for prototyping, which is just enforcing the old rule of “Use whatever tool you are most comfortable with” - and I’ve been on a streak with go these past months, for sure.

When it comes to Beam, however, please use Python or Java, as these SDKs are much, much more mature. I’ve done both, and Java has the edge when it comes to performance and features, but I find Python to be more fun to write (everything winds up being a dict).

We’ve also shown that you do not need a 100 node Hadoop cluster or Cloud-job to waltz through ~240GB in total. This entire thing ran on my Home Server, the humble bigiron.local, which rocks a Ryzen 2200G (4 cores, 4 threads), 32GB of non-ECC memory, 6 HDDs with ext4 and LUKS, behind a Mikrotik switch and Mikrotik RB4011 Ethernet-router. In other words, a relatively modest machine via Gigabit ethernet. The longest running task was by far copying data between my spinning drives!

I’ve also learned that my discipline regarding backups is good - nothing in this export wasn’t already on the server. You might find different result, if you are actually care to run this.

But maybe it inspires some folks to look into the field of Data Engineering - which, sadly, is often seen as a lesser Software Engineering discipline - and for those of y’all who are already in the field, maybe you learned something new.

All development and benchmarking was done under GNU/Linux [PopOS! 20.04 on Kernel 5.8] with 12 Intel i7-9750H vCores @ 4.5Ghz and 16GB RAM on a 2019 System76 Gazelle Laptop, using bigiron.local as endpoint