Introduction↑

In this article, I’ll document my process of building a home server - or NAS - for local storage, smb drives, backups, processing, git, CD-rips, and other headless computing.

Why a Home Server?↑

The necessity of a NAS these days can be questioned, given the cheap - or free - availability of cloud storage. However, getting into a dependency with an external vendor poses significant security risk for individuals that do not enjoy the same benefits a corporate account with big bills might receive, notably -

- Changes in storage tiers and costs (see Flickr limiting free user’s storage tier to 1,000 photos, from previously 1TB or Microsoft dropping unlimited storage for OneDrive - especially fun if you already have gigabytes, if not terabytes, stored there)

- Upload capacity with broadband connections (except for Google Fiber, no American ISP offers symmetric up/down links) - uploading my CD vinyl collection, even ripped as compressed MP3s @ ~70GB, would take me a easily half a day - (not to mention my 2TB Steam collection) and that is only a fraction of our available local storage)

- And hence, high-speed backups from all local devices, such as PCs, Macs, Routers, etc.

- Privacy concerns - while you can, naturally, uploaded encrypted files, you lose the benefit of automatic syncing in most cases

- Flexibility to run additional services such as a pi-hole (DNS ad blocker), monitoring software, local build server and git repositories, or VPN services

- Service outages on cloud services or your local internet

However, for the record - the server where you reading this article on does get backed up to AWS S3 via an encrypted duplicity backup (which is neither free nor user-friendly). There is no “one size fits all” solution.

As a preliminary note: Do not copy paste any of the commands without making sure all parameters match your system’s configuration!

Hardware↑

- CPU: AMD - Ryzen 3 2200G 3.5 GHz Quad-Core Processor

- Motherboard: Gigabyte - GA-AB350-GAMING 3 ATX AM4 Motherboard

- Memory: 2x Corsair - Vengeance LPX 8 GB (1 x 8 GB) DDR4-2400 Memory

- Storage: Western Digital - Green 240 GB M.2-2280 Solid State Drive

- Storage: 2x Western Digital - Red 6 TB 3.5” 5400RPM Internal Hard Drive

- Storage: 2x Western Digital - Red 3 TB 3.5” 5400RPM Internal Hard Drive

- Power Supply: EVGA - SuperNOVA G3 550 W 80+ Gold Certified Fully-Modular ATX Power Supply

- Case Fan: 2x Noctua - NF-F12 PWM 54.97 CFM 120mm Fan

- Case Fan: 2x Noctua - NF-R8 redux-1800 PWM 31.37 CFM 80mm Fan

- Case: Rosewill RSV-R4000, 4U Rackmount Server Case / Server Chassis, 8

The total price (as of 2019-04-06) is roughly $1,200 USD.

I’ve also added some existing hardware, like 2x 1TB Samsung HDDs and a PCI-to-SATA extension card.

Preparation↑

Make sure you have the follow tools available -

- A laptop or desktop running any GNU/Linux or MacOS (Windows instructions differ - you will need an ssh client like putty or MobaXTerm as well as unetbootin to burn the ISO)

- An ethernet cable

- A keyboard

- A screwdriver

- A USB thumb drive

- All server hardware

- (Optional) Small LCD screen and spare keyboard to access the drive if SSH won’t work for some reason

First, we’ll get ourselves a Debian 9 ISO and burn it to a USB Thumb Drive. Other operating systems are available - I like Debian for it’s stability and easy maintenance and already run several Debian boxes.

cd ~/Downloadswget https://cdimage.debian.org/debian-cd/current/amd64/iso-cd/debian-9.8.0-amd64-netinst.isosudo fdisk -l | grep -B 2 -A 15 "Flash"sudo dd bs=4M if=debian-9.8.0-amd64-netinst.iso of=/dev/sdf➜ Downloads sudo dd bs=4M if=debian-9.8.0-amd64-netinst.iso of=/dev/sdf73+0 records in73+0 records out306184192 bytes (306 MB, 292 MiB) copied, 11.6768 s, 26.2 MB/sHardware setup↑

This step is fairly straightforward. Assemble the hardware, plug in it, and make sure it posts. In the process, make sure the room you are using to assemble the system looks like a tornado went through it.

Cable management optional

Install Operating System↑

With your hardware connected to a screen, keyboard, and ethernet, it’s time to install the OS. Insert the flash drive, boot into it on the server hardware, and install Debian. I used my M.2 SSD with separate /home and /tmp partitions and enabled disk encryption with LUKS.

Software setup↑

Once the installation is completed, we can set up the software.

First, we need to configure our network. Take a backup of the configuration and edit the file with vi:

sudo cp /etc/network/interfaces /etc/network/interfaces.baksudo vi /etc/network/interfacesSomething like this should be the content for your interface file:

auto loiface lo inet loopback

iface eth0 inet static address 192.168.1.130 netmask 255.255.255.0 network 192.168.1.0 broadcast 192.168.1.255 gateway 192.168.1.1

sudo vi /etc/resolv.conf

nameserver 192.168.1.176Keep in mind that your IP configuration might be different. Since I am running a pi-hole on IP 192.168.1.176, my DNS configuration refers to that server. For your environment, you probably want to go with 1.1.1.1 and 1.0.0.1 as DNS tuple. You can always check on your other devices via $ ifconfig or similar commands.

Next, we’ll configure the hostname and host resolution and restart the network service.

My hostname is “bigiron”, which might or might not be a Marty Robbins and Fallout reference. You can choose whatever you like.

sudo echo bigiron > /etc/hostname

sudo vi /etc/hosts# Example127.0.0.1 localhost192.168.1.130 bigironBefore doing anything, we’ll restart the network service and test the connection. Make sure you can reach google.com.

sudo service networking restartif [[ $(hostname) == "bigiron" ]]; then echo "success"; else echo "failed"; fiping google.comThen, we’ll update our packages and install all required software:

sudo apt-get updatesudo apt-get upgradesudo apt-get install zsh \vim \git \openssh-server \parted \wget \curl \cryptsetup \mdadm \libcups2 samba samba-common cupsThe software we need to install here is fairly standard - zsh is going to be our shell, vim serves as editor, git is used to handle repositories, openssh-server is used for SSH connection, wget & curl are used for downloads and network tests, cryptsetup and mdadm are used for disk encryption and RAID arrays, and the samba dependencies are for file shares.

Disclaimer: There is a known vulnerability for wget, CVE-2019-5953.

There is a known vulnerability for wget, CVE-2019-5953

Next, we’ll configure oh-my-zsh, a neat little wrapper around zsh that is my default shell on all *NIX boxes.

sh -c "$(wget https://raw.githubusercontent.com/robbyrussell/oh-my-zsh/master/tools/install.sh -O -)"Now, we need to configure ssh to use the system remotely from our other machine.

sudo vim /etc/ssh/sshd_configAdd the following content (using your user name) and restart ssh. Please make sure you configure public/private key authentication in due time.

# UsersAllowUsers christian# LoggingSyslogFacility AUTHLogLevel INFO# Authentication:LoginGraceTime 2mPermitRootLogin noStrictModes yesMaxAuthTries 6MaxSessions 10

service ssh restartHard drive setup↑

Congratulations, your system is now operational. Granted - it doesn’t do anything. But we’ll change that in a spiffy!

You can now connect to your system using SSH (which is what we are going to do).

One of our most command commands is going to be the following:

sudo fdisk -lservice ssh restartDisk /dev/sdh: 5.5 TiB, 6001175126016 bytes, 11721045168 sectorsUnits: sectors of 1 \* 512 = 512 bytesSector size (logical/physical): 512 bytes / 4096 bytesI/O size (minimum/optimal): 4096 bytes / 4096 bytesDisklabel type: gptDisk identifier: 46AAB764-3004-481A-AA2D-5D751D996AC1

Device Start End Sectors Size Type/dev/sdh1 2048 11721045134 11721043087 5.5T Linux filesystemservice ssh restartThis shows us the physical disks in the system, as well as their partitions. As I’ve mentioned before - do not simply copy paste these commands. Otherwise you will risk losing data and messing up your system.

Make sure you always take note of your disks’ identifiers (e.g., /dev/sda) and UUIDs.

Do not copy paste any of the commands without making sure all parameters match your system’s configuration

With that out of the way, we will need to add partitions to our first set of hard drives and format them. This will delete all data on the disks.

sudo parted /dev/sdb(parted) mklabel gptWarning: The existing disk label on /dev/sdc will be destroyed and all data on this disk will be lost. Do you want to continue?Yes/No? y(parted) mkpart primary ext 0% 100%(parted) exitsudo mke2fs -t ext4 /dev/sdb2Once that is done, we need to create our RAID-1 array as such. We use RAID-1 to protect ourselves against disk failures. A RAID-1 array protects against drive failures - it is not a backup!

A RAID-1 array protects against drive failures - it is not a backup!

mdadm --create --verbose --level=1 --metadata=1.2 --raid-devices=2 /dev/md/6TB /dev/sdb1 /dev/sdc1You can check the configuration as well as the sync status of your RAID-1 array as such:

➜ ~ sudo mdadm --detail /dev/md127/dev/md127: Version : 1.2 Creation Time : Sat Apr 6 18:27:22 2019 Raid Level : raid1 Array Size : 5860390464 (5588.90 GiB 6001.04 GB) Used Dev Size : 5860390464 (5588.90 GiB 6001.04 GB) Raid Devices : 2 Total Devices : 2 Persistence : Superblock is persistent

Intent Bitmap : Internal

Update Time : Sat Apr 6 18:27:22 2019 State : clean, resyncing Active Devices : 2Working Devices : 2 Failed Devices : 0 Spare Devices : 0

Resync Status : 0% complete

Name : bigiron:6TB (local to host bigiron) UUID : ffafd947:3c116230:a1e40521:332156c7 Events : 1

Number Major Minor RaidDevice State 0 8 17 0 active sync /dev/sdb1 1 8 33 1 active sync /dev/sdc1Encryption with LUKS↑

Then, we’ll add LUKS encryption to the array:

sudo cryptsetup luksFormat /dev/md127sudo cryptsetup luksOpen /dev/md127 6TB\_LUKSsudo mkfs.ext4 /dev/mapper/6TB\_LUKSsudo mkdir /mnt/6TBsudo mount /dev/mapper/6TB\_LUKS /mnt/6TBOnce that is done, we’ll add a key file to make sure we don’t need to punch in the password every time.

This this step, I am using an external USB thumb drive and hence am mounting /dev/sdd1 to /mnt/usb. You can also keep the key file on the system, but that would invalidate the point of having an encrypted disk in the case of theft.

sudo mount /dev/sdc1 /mnt/usbsudo dd bs=512 count=4 if=/dev/random of=/mnt/usb/keyfile iflag=fullblock4+0 records in4+0 records out2048 bytes (2.0 kB, 2.0 KiB) copied, 891.521 s, 0.0 kB/ssudo chmod 600 /mnt/usb/keyfilesudo cryptsetup luksAddKey /dev/md127 /mnt/usb/keyfile --key-slot 1Wonderful. Now, let’s make sure that the thumb drive containing the key gets mounted on boot by editing /etc/fstab

sudo fdisk -lsudo blkid /dev/sdc1 | awk -F'"' '{print $2}'sudo vim /etc/fstab

UUID=b796c692-2ba5-49cf-a45d-dbd62228dd98 /mnt/usb auto nosuid,nodev,nofail 0 0Then, we need to add the actual encrypted disk to /etc/fstab as well as /etc/crypttab.

# Get UUIDsudo cryptsetup luksDump /dev/md127 | grep "UUID"

# Edit /etc/crypttabsudo mdadm --detail /dev/md127sudo vim /etc/crypttab# 6TB_LUKS UUID=e4cd8646-375d-4d84-886c-ba80b31698ad /mnt/usb/keyfile lukssudo vim /etc/fstab# /dev/mapper/6TB_LUKS /mnt/6TB ext4 defaults 0 2In my case, I have only enabled this for the data drives, not for the boot drive. This is a matter of personal preference - I have a small 7” LCD on the 19” rack, including a keyboard, and simply punch in the LUKS key code on reboot. This won’t work you are not home, but leaving the thumb-drive in the system while you are away won’t help theft prevention of data. Feel free to send me your own best practices.

With all that done, you can test the setup by mounting everything in /etc/fstab by running:

sudo mount -aRepeat this process for every RAID array in the system. In my case, that would be 2.

Furthermore, to persist names for existing arrays, follow these steps:

sudo mdadm --stop /dev/md126sudo mdadm --assemble /dev/md3 --name=3TB --update=name /dev/sda /dev/sdbsudo mdadm -Db /dev/md3 >> /etc/mdadm/mdadm.confsudo update-initramfs -uOn a side-node - if you have existing drives, for instance from your desktop PC, make sure to back up all your data to a different disk, as setting this up will delete all data. You can do this as such:

sudo rsync --partial -T /mnt/6TB/tmp -azh /mnt/3TB/ /mnt/6TB/ --exclude=".Trash-1000" --progressOn a related note, since I transferred an existing RAID-1 array, I had some massive drive issues that resulted in odd behavior (like timeouts on the READ() call in the kernel, as followed by strace - please don’t ask me why) - if you want to debug issues like these, the following commands might come in handy.

You can see the files being accessed by commands like rsync or cp through /proc with the specific PID of a process:

ps aux | grep rsyncwatch sudo ls -l /proc/1446/fdEvery 2.0s: sudo ls -l /proc/1446/fd bigiron: Thu Apr 11 17:36:55 2019

total 0lrwx------ 1 root root 64 Apr 11 17:03 0 -> /dev/tty1lrwx------ 1 root root 64 Apr 11 17:03 1 -> /dev/tty1lrwx------ 1 root root 64 Apr 11 17:03 2 -> /dev/tty1lr-x------ 1 root root 64 Apr 11 17:24 3 -> /mnt/3TB/memes/2019/04/memes_if_i_die_before_game_of_thrones_comes_out/928_meme.jpglrwx------ 1 root root 64 Apr 11 17:03 4 -> socket:[18863]lrwx------ 1 root root 64 Apr 11 17:03 5 -> socket:[18864]Also, using strace, you can debug very odd, low-level issues like mine:

strace cp broken.txt broken2.txtecve("/bin/cp", ["cp", "broken.txt", "broken2.txt"], [/* 24 vars */]) = 0brk(NULL) = 0x55adfb96b000access("/etc/ld.so.nohwcap", F_OK) = -1 ENOENT (No such file or directory)access("/etc/ld.so.preload", R_OK) = -1 ENOENT (No such file or directory)open("/etc/ld.so.cache", O_RDONLY|O_CLOEXEC) = 3fstat(3, {st_mode=S_IFREG|0644, st_size=35999, ...}) = 0mmap(NULL, 35999, PROT_READ, MAP_PRIVATE, 3, 0) = 0x7f82ba539000close(3) = 0access("/etc/ld.so.nohwcap", F_OK) = -1 ENOENT (No such file or directory)open("/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libselinux.so.1", O_RDONLY|O_CLOEXEC) = 3read(3, "\177ELF\2\1\1\0\0\0\0\0\0\0\0\0\3\0>\0\1\0\0\0000k\0\0\0\0\0\0"..., 832) = 832fstat(3, {st_mode=S_IFREG|0644, st_size=155400, ...}) = 0mmap(NULL, 8192, PROT_READ|PROT_WRITE, MAP_PRIVATE|MAP_ANONYMOUS, -1, 0) = 0x7f82ba537000mmap(NULL, 2259664, PROT_READ|PROT_EXEC, MAP_PRIVATE|MAP_DENYWRITE, 3, 0) = 0x7f82ba0f7000mprotect(0x7f82ba11c000, 2093056, PROT_NONE) = 0mmap(0x7f82ba31b000, 8192, PROT_READ|PROT_WRITE, MAP_PRIVATE|MAP_FIXED|MAP_DENYWRITE, 3, 0x24000) = 0x7f82ba31b000mmap(0x7f82ba31d000, 6864, PROT_READ|PROT_WRITE, MAP_PRIVATE|MAP_FIXED|MAP_ANONYMOUS, -1, 0) = 0x7f82ba31d000close(3) = 0...Network shares↑

Now, we’ll set up network shares with samba. This will allow all devices in the network to access shares on the server.

All we need to do is add a new user for samba (as smb users are separate from the host system’s users), backup our samba configuration and add shares, including valid users as such:

sudo smbpasswd -a christiansudo cp /etc/samba/smb.conf /etc/samba/smb.conf.baksudo vim /etc/samba/smb.confsudo service smbd restartAnd:

[global] server min protocol = NT1 ; server max protocol = SMB3

...

[6TB]path = /mnt/6TBbrowseable = yeswriteable = yesvalid users = christianTest your setup by mounting the smb drive on a different computer. The below example is for Arch Linux. Replace the username and password accordingly.

sudo pacman -S smbclientsudo mkdir -p /mnt/shares/6TB-ServerAdd a secured, read-only file for root to store your passwords:

sudo mkdir -p /etc/samba/credentials/sudo vim /etc/samba/credentials/sharesudo chown root:root /etc/samba/credentialssudo chmod 700 /etc/samba/credentialssudo chmod 600 /etc/samba/credentials/shareIni:

username=myuserpassword=mypassAnd try connecting:

sudo mount -t cifs //192.168.1.213/6TB /mnt/shares/6TB-Server -o credentials=/etc/samba/credentials/share

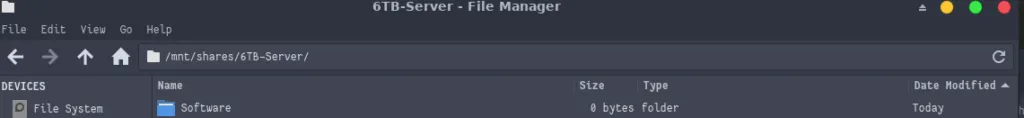

Mounted drive on Arch Linux with KDE

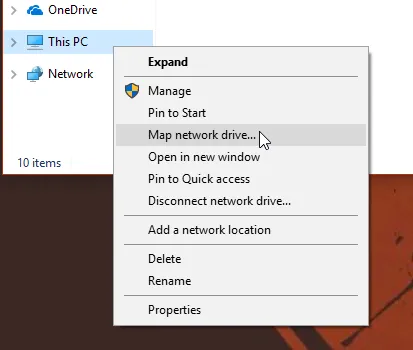

I hate to admit it, but Windows makes it a bit easier. :) Please see below for the steps (for Windows 10 Pro):

Right-click on “This PC” and “Map network drive”

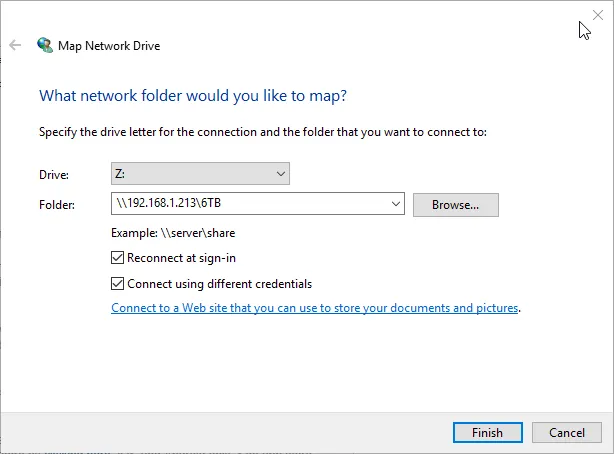

Map Drive

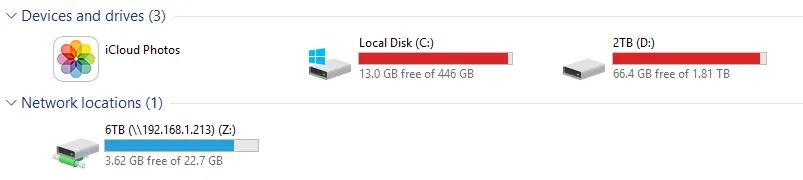

Mapped Drive (the size might be off - this happened due to invalid permissions)

Backups↑

Last but not least, we’ll enable automatic updates for a GNU/Linux machine.

This is done with an encrypted duplicity backup. Make sure you store your GPG keys somewhere secure, like an encrypted USB drive.

sudo suapt-get install duplicity gpggpg --gen-keygpg --list-keys# Take the GPG_KEY from heretouch /root/backup_arch.shchmod +x /root/backup_arch.shvim /root/backup_arch.shScript:

#!/bin/shexport GPG_KEY=YOUR_KEY_HERE

if [ "${EUID}" -ne 0 ]; then echo "You're not root" exitfis# Check if external drive is mountedSHARE=/mnt/shares/6TB-Serverif [[ -z $(mount -t cifs | grep "${SHARE}") ]]; then echo "Disk not connected, aborting" exit 1else echo "Disk available, continuing..."fi#MOUNTPONT=$(findmnt -rn -S UUID="${UUID}")if [ -z "${MOUNTPONT}" ]; then mount -t cifs //192.168.1.213/6TB /mnt/shares/6TB-Server -o credentials=/etc/samba/credentials/share RET=$?fi# Check successif [ $RET -ne 0 ]; then echo "Mount failed!" exit 1fi

# Delete any older than 1 month#duplicity remove-older-than 7D --force --encrypt-key=9CE17035 --sign-key=9CE17035 file:///mnt/5TB/arch_backup/

# Make the regular backup# Will be a full backup if past the older-than parameterduplicity --full-if-older-than 7D --encrypt-key=${GPG_KEY} --sign-key=${GPG_KEY} -exclude=/proc --exclude=/lost+found --exclude=/backups --exclude=/mnt --exclude=/sys --exclude=/opt/virtual / file:///mnt/shares/6TB-Server/backups/arch/

export GPG_KEY=You can know schedule this with cron (the below command will run it every day at midnight):

crontab -e0 0 * * * /root/backup_arch.sh > /var/log/backup/$(date --iso)_backup.logFurther Steps↑

There are a lot more steps that you can take to make your server fully operational.

Here are some ideas -

- Plex or other home media shares to access your media on e.g. your AppleTV

- Running your own git server

- Running your own build server

- Running nextCloud

- Enabling wireguard or other VPNs for external access

- Enable rotating logs and log-backups

- Enable a duplicity backup pipeline to an external hard drive to safeguard against fires, electrical issues, or theft (a RAID-1 array protects against drive failures - it is not a backup!)

Furthermore, I strongly recommend setting up the following security best practices:

- Enable ssh login via public/private keys only

- Enable apparmor to restrict service account’s permissions (this can be very, very time intensive and may break existing software)

- Enable proper iptable rules

- Secure your outgoing and incoming ports on your router and physical network (switches)

- Secure your samba configuration

Conclusion↑

Running a home server can be taxing on free time and costs, but does allow for some powerful computing capabilities in your own home. Following similar steps like the ones highlighted above allow you to properly own your data, have control over your backups, and be independent of Cloud providers.

It is also a wonderful learning experience for everyone who has interest in GNU/Linux and Sysadmin tasks, but doesn’t want to be limited to small computing power (Raspberry Pi) or purely on fun projects (like running a barebones Debian on an old laptop).

While a regular external hard drive for Backups and Cloud services for anything else might be plenty for most people, if you have the energy to be your own admin, I can highly recommend putting a 19” rack in your house.

Disclaimer: In case you are married, you might need couples counseling after putting 100lbs of solid steel and a plethora of ethernet cables in your office.

Final Setup